Lunch was at Pier W in Lakewood’s Winton Place on a cold, gray day. Quite by chance, we were seated facing downtown Cleveland, a hazy outline that rose like a ghost above the frigid lake.

The view was made for a photograph. Dick Feagler said it before I could.

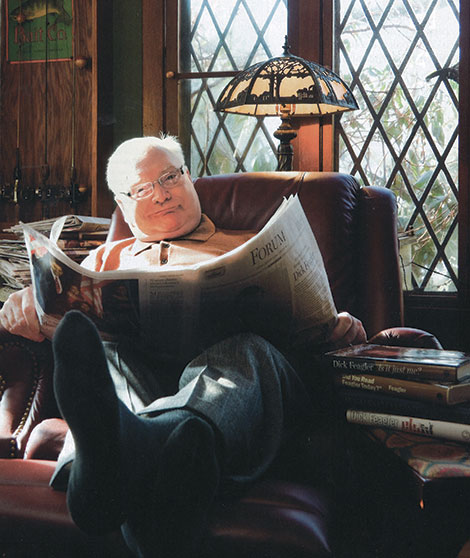

The symbolism was apparent: Cleveland was Feagler’s city. It belonged to him more than it ever belonged to the politicians and businesspeople who governed it. Feagler, 70, spent a lifetime preaching common sense to a city that always seemed short on it.

In January, Feagler’s last regular column appeared in The Plain Dealer. Probably no columnist in Cleveland’s history ever captured the town as Feagler did in his

38-year career, a time when newspapers werethe soul of the town.

At lunch, he picked up the check, as he’d done for a writer doing an advance on his obituary. Feagler never saw a lead he didn’t write.

He penned more than 4,000 newspaper columns and worked as a reporter, magazine writer, talk show host and television anchorman. He will remain the host of Feagler & Friends on WVIZ-TV.

Feagler and I go back to the days when ties were an inch wide and cigarette butts littered the newsroom floor. We were once competitors, he a reporter at The Cleveland Press, I at The Plain Dealer. My memories of those times are not so much nostalgic as anxious — wondering where the Press would strike next. As a reporter, I worried about getting scooped on my beat. Later, as city editor, I feared thePress was on to some screaming headline that would humiliate us all, down to the lowest copy boy. Nobody thought about money then, just a good Page One story.

So on this cold winter day with the city a mezzotint of gray, we talked about those times and about Feagler’s long career.

The view was made for a photograph. Dick Feagler said it before I could.

The symbolism was apparent: Cleveland was Feagler’s city. It belonged to him more than it ever belonged to the politicians and businesspeople who governed it. Feagler, 70, spent a lifetime preaching common sense to a city that always seemed short on it.

In January, Feagler’s last regular column appeared in The Plain Dealer. Probably no columnist in Cleveland’s history ever captured the town as Feagler did in his

38-year career, a time when newspapers werethe soul of the town.

At lunch, he picked up the check, as he’d done for a writer doing an advance on his obituary. Feagler never saw a lead he didn’t write.

He penned more than 4,000 newspaper columns and worked as a reporter, magazine writer, talk show host and television anchorman. He will remain the host of Feagler & Friends on WVIZ-TV.

Feagler and I go back to the days when ties were an inch wide and cigarette butts littered the newsroom floor. We were once competitors, he a reporter at The Cleveland Press, I at The Plain Dealer. My memories of those times are not so much nostalgic as anxious — wondering where the Press would strike next. As a reporter, I worried about getting scooped on my beat. Later, as city editor, I feared thePress was on to some screaming headline that would humiliate us all, down to the lowest copy boy. Nobody thought about money then, just a good Page One story.

So on this cold winter day with the city a mezzotint of gray, we talked about those times and about Feagler’s long career.

Cleveland Magazine: Are you going to miss the column? After all, it’s been a part of you and the town for 38 years.

Dick Feagler: No, especially since they made me write two goodbye columns. I didn’t want a long goodbye. It was hard work.

It is going to be interesting to see how my instincts react to some occurrence, and I think,Well, that might not be a bad column, then not be able to write it. But it’s time to go. The town has plenty of young columnists with fresh ideas.

It is going to be interesting to see how my instincts react to some occurrence, and I think,Well, that might not be a bad column, then not be able to write it. But it’s time to go. The town has plenty of young columnists with fresh ideas.

CM: I was always interested in the readership your column had. I could work on a story for months and only get a letter or two, but your column drew incredible response.

Feagler: It was a bad day if I only got 50 or 60 responses. The most I ever got was over a column I wrote about breast-feeding at Wal-Mart. There had to be 600 calls. It was off the charts.

CM: What kind of relationship did you have with readers?

Feagler: I never thought that much about it until the day I got a call from a woman who said she was dying of cancer. Every day she listened for the “plop” of the paper at her doorstep.

She told me she waited daily to see what I had to say. If I was that important to that woman, then maybe God wanted me to do this.

She told me she waited daily to see what I had to say. If I was that important to that woman, then maybe God wanted me to do this.

CM: Did you set out to be a newspaper columnist?

Feagler: No, I was going to be the Great American Novelist. But two things happened on the way to the book: I got married and had a couple of kids. Then I had to make some money. And that is how I ended up in newspapers.

CM: How did you get the column?

Feagler: I had been writing features for about eight years. They wanted to reward me. They offered me the opportunity to become an assistant city editor or become a columnist. The world was full of assistant city editors, but getting a column was like being given a scepter. You could write about anything. Later, when I thought about it, that was no easy job.

CM: How hard was it writing a column three times a week?

Feagler: I figured I’d do what I was capable of and not worry about it. You took it a column at a time. When you write columns for 10 years, it occurs that not everyone can do that.

CM: How has the town changed in your time?

CM: How has the town changed in your time?

Feagler: Terribly. When you and I started on the newspapers, we had no idea that we were already covering a dying town. The move to the suburbs changed everything and took the life out of the city. Remember how we used to hang around downtown after work, maybe go to the Theatrical and see everyone worth seeing in town? Now the streets are empty before it’s dark. It’s sad.

CM: Best column you’ve ever written?

Feagler: Come on, you know better than that. You work at the column hoping to make the next deadline. You’re not thinking of “bests.”

CM: Magazines like to ask questions like that these days.

CM: Best column you’ve ever written?

Feagler: Come on, you know better than that. You work at the column hoping to make the next deadline. You’re not thinking of “bests.”

CM: Magazines like to ask questions like that these days.

Feagler: Well, a couple come to mind that survived in one way or another. The one about Aunt Ida and Christmas was published annually in The Plain Dealer for a time. They made a play out of it, and I check each year with my wife, Julie, to see if it still brings tears.

Then there was Mrs. Figment, who in a way was really my Aunt Emma. The paper was sending me to Japan to cover the Orchestra, and I wanted some time off before the trip. Bill Tanner, the city editor, wouldn’t hear of it, so out of pique I wrote about Mrs. Figment, who was always lecturing me. It stuck, and readers loved it. Eventually I had to kill her off. I was getting too old to be lectured.

CM: Biggest story of your time?

Then there was Mrs. Figment, who in a way was really my Aunt Emma. The paper was sending me to Japan to cover the Orchestra, and I wanted some time off before the trip. Bill Tanner, the city editor, wouldn’t hear of it, so out of pique I wrote about Mrs. Figment, who was always lecturing me. It stuck, and readers loved it. Eventually I had to kill her off. I was getting too old to be lectured.

CM: Biggest story of your time?

Feagler: Race. It changed the town. I had a disagreement with a colleague last year, a black columnist [Phillip Morris] who took me to task for saying that race drove people out of town. And I mean not just white people, but black people as well. How could you look back on the town and not be honest about what’s happened?

I grew up at a time when blockbusting was going around in our neighborhood, the Lee-Harvard area, so race was always part of what Cleveland was about to me. How about all those stories we covered on Murray Hill, the riots, school busing and the Carl Stokes years? That was all about race.

I grew up at a time when blockbusting was going around in our neighborhood, the Lee-Harvard area, so race was always part of what Cleveland was about to me. How about all those stories we covered on Murray Hill, the riots, school busing and the Carl Stokes years? That was all about race.

CM: You wrote for the Press until it closed in 1982, and I remember you telling me later you never quite felt comfortable working for The Plain Dealer.

Feagler: That’s true, it was never my paper. You know better than anyone else what I mean. Remember how the Press and Plain Dealer people hated each other? But when I finally went to The Plain Dealer, I was treated well.

CM: Was it just the competition that caused the hostility?

Feagler: Frankly, you guys had a lot of asses. Unfulfilled poets, philosophers, people who talked more about writing than actually wrote and huge, huge egos. You guys were weird and overstaffed. At one point, Newsweek wrote that you guys were young tigers. We could never figure out why. At our place, people did not have those pretensions. They just covered the news and had to write more than one story a day. You guys could go a whole year without writing a story. What was that about?

CM: Well, we thought that some of your people were kind of off the wall, too — always loud and pushy, whether it was at City Hall, a murder or at a bar. Some of your guys had food spots on their ties, too.

Feagler: It was never a business about manners — even though you used middle initials in bylines, which was another thing that annoyed us. That is all changed now. There are no characters.

CM: What was it like working for [Press editor] Louie Seltzer?

Feagler: Louie thought he was put on earth to battle common causes. Louie knew the city, cared about it in a way that few others could. Seltzer liked to think the paper took its readers from cradle to grave. There were those in town who did not like him, but they generally respected him. Nobody ever replaced him.

CM: You covered a lot of politicians. Did you have a favorite?

Feagler: I liked Carl Stokes. He had charm, spoke well, and when he walked into a room, he lit it up like a rock star. Nationally — and people will choke on this — the politician I enjoyed covering was [Alabama Gov.] George Wallace. On the press plane, he’d walk down the aisle and talk with all of us. He was very cordial. But the moment he got in front of a crowd, he would point to us and say that we were the ones ruining the country. It was a game.

CM: What are you going to do now?

Feagler: Maybe I’ll write that novel. I always wanted to write one about Cleveland. I enjoy doing Feagler & Friends and will continue to do that.

CM: Are you sure this is it for the column?

Feagler: When I left The Plain Dealer, [editorial director] Brent Larkin said if the mood struck me, he would give me the princely sum of $50 for an occasional column. Doesn’t that tell you something?

Feagler: That’s true, it was never my paper. You know better than anyone else what I mean. Remember how the Press and Plain Dealer people hated each other? But when I finally went to The Plain Dealer, I was treated well.

CM: Was it just the competition that caused the hostility?

Feagler: Frankly, you guys had a lot of asses. Unfulfilled poets, philosophers, people who talked more about writing than actually wrote and huge, huge egos. You guys were weird and overstaffed. At one point, Newsweek wrote that you guys were young tigers. We could never figure out why. At our place, people did not have those pretensions. They just covered the news and had to write more than one story a day. You guys could go a whole year without writing a story. What was that about?

CM: Well, we thought that some of your people were kind of off the wall, too — always loud and pushy, whether it was at City Hall, a murder or at a bar. Some of your guys had food spots on their ties, too.

Feagler: It was never a business about manners — even though you used middle initials in bylines, which was another thing that annoyed us. That is all changed now. There are no characters.

CM: What was it like working for [Press editor] Louie Seltzer?

Feagler: Louie thought he was put on earth to battle common causes. Louie knew the city, cared about it in a way that few others could. Seltzer liked to think the paper took its readers from cradle to grave. There were those in town who did not like him, but they generally respected him. Nobody ever replaced him.

CM: You covered a lot of politicians. Did you have a favorite?

Feagler: I liked Carl Stokes. He had charm, spoke well, and when he walked into a room, he lit it up like a rock star. Nationally — and people will choke on this — the politician I enjoyed covering was [Alabama Gov.] George Wallace. On the press plane, he’d walk down the aisle and talk with all of us. He was very cordial. But the moment he got in front of a crowd, he would point to us and say that we were the ones ruining the country. It was a game.

CM: What are you going to do now?

Feagler: Maybe I’ll write that novel. I always wanted to write one about Cleveland. I enjoy doing Feagler & Friends and will continue to do that.

CM: Are you sure this is it for the column?

Feagler: When I left The Plain Dealer, [editorial director] Brent Larkin said if the mood struck me, he would give me the princely sum of $50 for an occasional column. Doesn’t that tell you something?