Kimberly Armbruster let the phone fall from her ear and cursed.

Her boyfriend had been on the line. He had ventured into her apartment for something. “Babe, your lights are shut off,” he said. Armbruster let out a sigh and said little more than, “OK.”

She hung up and returned to class, feeling downtrodden.

“I already have problems, and when I have more problems added to my problems, it just makes me freak out, even if it’s stupid little things. It’s just like, layers of my life,” Armbruster recalls. “I was like, ‘Of course they got shut off. What else?’ ”

This was supposed to be her new start. She had worked so hard for this, struggled so much for it, and now she was finally here, in Clark Hall, on the campus of Case Western Reserve University. Armbruster, who had grown up in and out of the Salvation Army shelter, who had run away from her parents at 13, who got her GED from Seeds of Literacy at 19, who had been forced to wait until she was 24, independent of her parents, to start college at Cuyahoga Community College. Who had found, to her surprise, that she was actually good at school, that her quiet and resolute demeanor earned her A’s, that her A’s could get her into a miraculous transfer program. Her, Kimberly Armbruster, with the determined smile and dimpled chin. By the summer of 2018, she had made it into one of the top 50 colleges in the country. It was her own little slice of the American dream.

But her utility bills still dogged her. For years, she had juggled payments, spending as wisely as she could on rent, food and books. Her only source of regular income was her monthly Social Security payment, and the infrequent refunds and stipends she got from school. Sometimes that was enough to pay for her life and her power and gas bills. Other times, there was not enough money to go around.

That was especially true when her Cleveland Public Power bills came due. She had moved into her house, the bottom level of a duplex in Cudell, in 2014. Her CPP bills were cheaper then, she recalls, often around $40 or $50. She could always pay them on time. But over the years, the amount CPP charged her had gone up. “At the beginning, my bill was doable, I was paying my bill regularly,” says Armbruster. “After it got over $100 is when I started having problems.”

As her bills creeped up, Armbruster began to put off paying them until she got tuition refunds from her school. Sometimes, she waited up to four months, running the risk of a shut-off. It was a gamble, and she sometimes lost.

CPP turned off her power twice, once during a particularly cold fall. She was able to stay with her boyfriend, who lived on the upper level of the duplex. His CPP power was also turned off, but he borrowed money from family to turn it back on. A whole month passed before Armbruster’s school refund arrived and her half of the house saw light again.

And now here she was, at the very start of her new beginning, repeating history. She dreaded returning to that darkened house, fumbling for doorknobs, opening the fridge to find the food turning dank inside. After class let out, she put off going home. She stayed on campus for the rest of the day, nestling into her favorite couch at the Tinkham Veale University Center. She browsed the internet, the thought gnawing in the back of her head: I won’t have this at home either. Eventually, she made her way to the GCRTA Red Line station and rode the subway home. She went straight to her boyfriend’s place. “I just got home, unwound, got comfy, and was talking about, like, ‘What am I going to do?’ and trying to come up with a plan,” she says.

Armbruster decided to use most of her summer stipend, which her academic program, the Cleveland Humanities Collaborative, had given her to acclimate to school, to pay off everything she owed to CPP.

“Every time they shut you off, you can’t give them a little bit. You can’t give them half of it, or close to the total. You have to give them the full balance. I’ve learned that,” she says. “When I was paying my bill, they were accepting what I was giving them and still shut me off. I took that as, well, ‘You’ll get your payment in full when I’m able to give to you in full.’ ”

She put the payment through on Aug. 6, 2018, three days after the summer program ended. It was the largest payment she had made in a long time: $717.98. But sending that number down to zero was a relief.

“I was about to start at Case and I wanted a fresh start. That’s how I feel every time I pay my bills completely off. Like, OK, this is a fresh start and I’m never going to let it get to this again,” says Armbruster. “But it always happens that way.”

Armbruster is far from the only one struggling to keep up with CPP and other bills. According to a 2016 report by the American Council For an Energy-Efficient Economy, Cleveland ranks 10th-worst out of 48 major cities for the largest energy burdens on low-income people. Low-income households in Cleveland spend about 8.5% of their annual income on utilities; the norm is 3.5%.

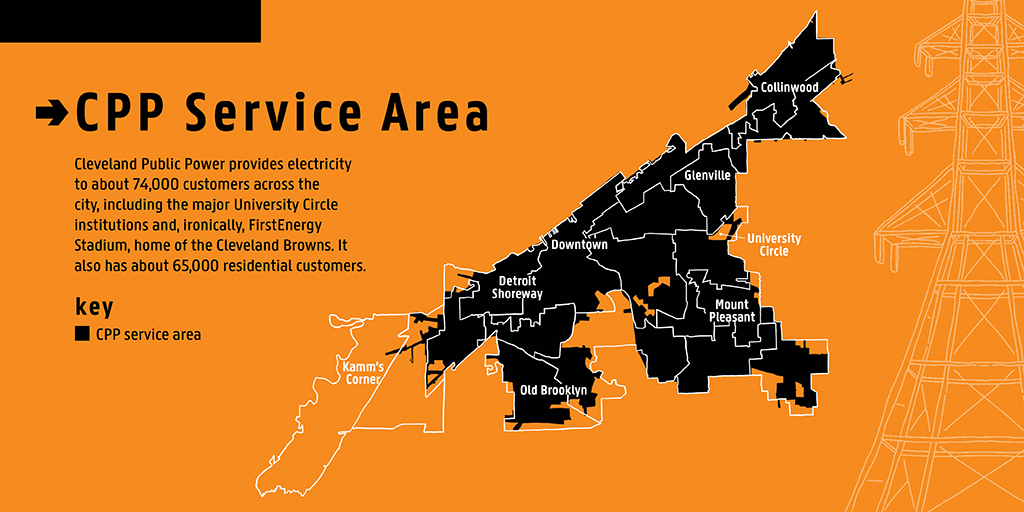

Unlike other cities, however, Cleveland has what is supposed to be a safeguard against high energy costs: Cleveland Public Power. The storied utility, owned by the city, has power lines stretching into nearly 74,000 homes and businesses across the East and West sides of Cleveland. About 65,000 CPP customers, like Armbruster, are residential. CPP was founded in 1904 with the explicit purpose of keeping energy prices low for everyone by setting them below investor-owned competitors. But CPP’s bills have soared higher and higher, and the least-advantaged Clevelanders are paying the price.

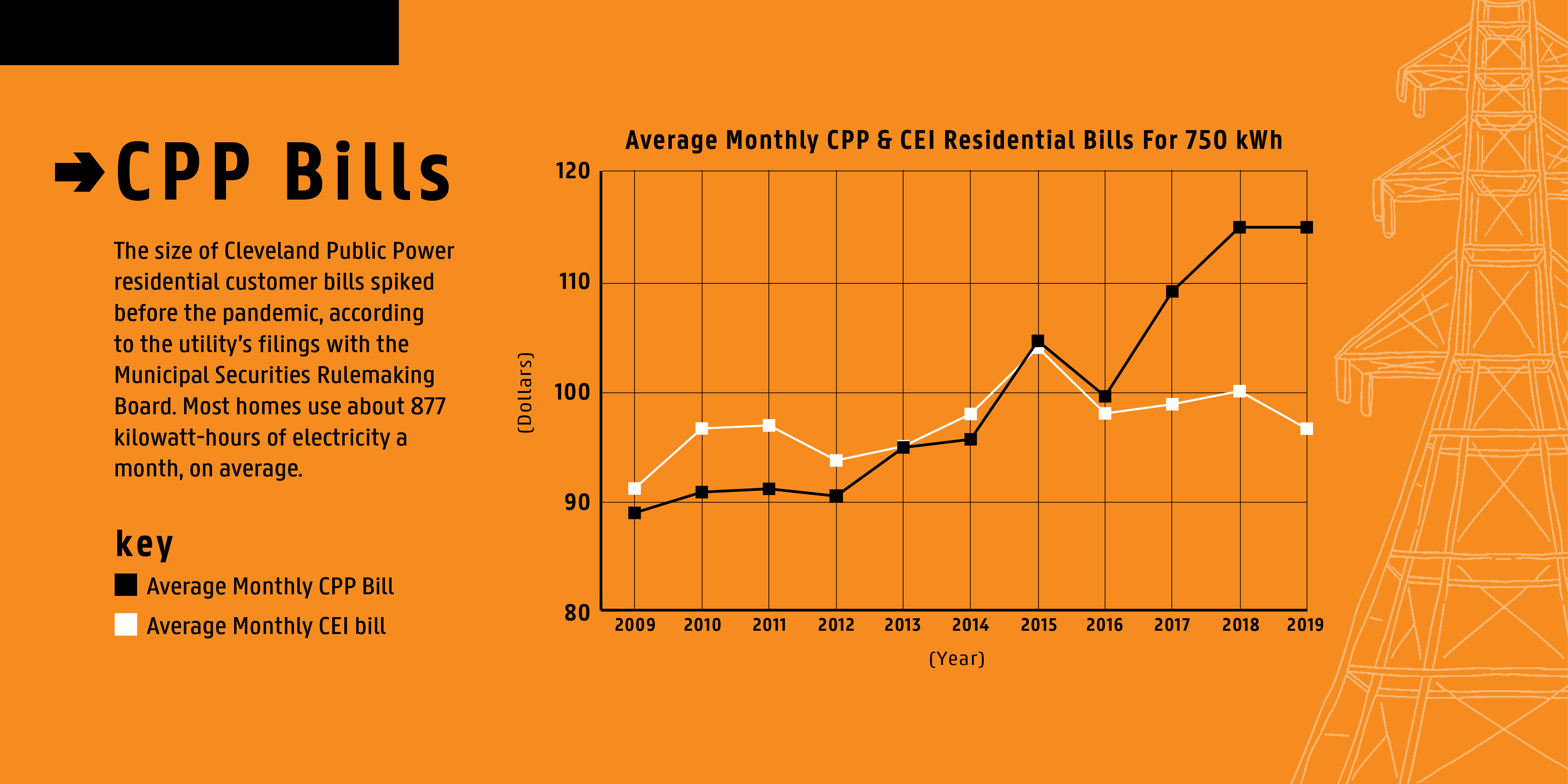

In the years leading up to the pandemic, CPP residential customers saw a large spike in their bills. CPP’s disclosures to its bondholders, available through the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, show that the average monthly bill a CPP residential customer paid for 750 kilowatt-hours of electricity increased from $90.39 in 2012 to $114.88 in 2019. The sharpest increase came from 2016 to 2018, when the average monthly bill shot up by more than $15.

CPP’s customers are struggling because of the utility’s self-inflicted wounds. CPP has let its prices soar because of 50-year deals to buy power, which are pulling the utility into a “death spiral” that consultants warned about more than a decade ago. That spiral was already gathering speed before the pandemic and was accelerated by a campaign financed by CPP’s competitor, FirstEnergy.

The number of CPP shut-offs for nonpayment also increased from 2017 to 2019, following a sharp spike in CPP bills. By 2017, the average monthly CPP residential bill had grown to $109.04. Data supplied to Cleveland Magazine by the independent grassroots advocacy group Utilities For All, which acquired it through public records requests reviewed by the magazine, shows that the number of residential CPP customers whose service was turned off for nonpayment more than doubled from 2017 to 2018, going from 3,646 to 7,746. By 2019, 8,253 overall CPP customers, including commercial and industrial, had experienced a shut-off.

Cleveland Magazine detailed all of the findings in this story, point-by-point, in an email to a CPP spokesperson on Feb. 4 and requested an interview with the CPP commissioner or Martin Keane, the head of the Department of Public Utilities. That interview request was denied. After multiple follow-ups via email and telephone seeking a written response, which the magazine gave CPP one week to formulate, CPP declined to comment.

It looked as if the wave of shut-offs would continue into 2020. But the pandemic brought an unexpected reprieve. As the country shut down last March, Mayor Frank Jackson announced a moratorium on shut-offs for city-controlled utilities, including CPP. No one would lose power or water if they couldn’t pay. Shut-off customers were even reconnected.

The moratorium was a godsend for Armbruster. She had always lived in fear of the CPP trucks that rumbled down her street. But she didn’t have to worry during the moratorium. When the lights flickered, she’d call to check on the situation, and found relief. “I would call, and [ask] ‘Is there a power outage?’ ” she says. “Thank God.”

But that moratorium ended on Dec. 1, 2020. Shut-offs can now technically resume, though the city has said it will be following its informal policy not to shut off utilities during the “winter months.” (CPP declined to specify on which date or under what weather conditions shut-offs would resume.)

Warm weather could bring back hardship for CPP’s least-advantaged customers. Research by Indiana University shows that 3.8 million Americans could not pay at least one energy bill since last May. And in Cleveland, where before the pandemic 32% of adults lived in poverty, a Cleveland State University study found that the city ranked fourth worst for pandemic job losses in the country.

Many Clevelanders who were struggling to pay their utility bills before the pandemic found it doubly difficult as the moratorium expired in December. Data acquired by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative in November found that 28,500 CPP customers, more than 35% of CPP’s customer base, were at least one month behind.

Now the moratorium is gone, and the coronavirus recession is set to continue into the spring and summer. Many CPP customers will have even less ability to pay their bills than before. In early January, as Armbruster headed back to school for a final semester of Zoom classes, she owed CPP $383.06.

“I’m not in it to get rich. I just want to survive and not have my lights off and have food in my belly. I just want the basic necessities. I don’t care about vacationing and fancy cars,” says Armbruster. “I just want to live.”