Everyone knows Superman.

He soars through the air in those red and blue tights, an “S” emblazoned on his muscled chest and a cape billowing behind. As the Man of Steel, he flicks bullets away. He speeds faster than locomotives. He wallops, kabooms and pows the bad guys. He stands before the rippling red, white and blue as the last son of Krypton and the defender of truth, justice and the American way.

As pre-phone booth Clark Kent, he masquerades as an everyday man. Still tall and handsome but somewhat diminished, our mild-mannered hero wears glasses and a tidy suit as a reporter at the Daily Planet. An empowerment fantasy given body, he lives our best instincts and finest ideals.

As Clevelanders, we know Superman better than most. The creation of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two Jewish high school students from Glenville, Superman is also one of us. So we tell others (incorrectly) that the art deco AT&T Huron Road Building is the model for Metropolis’ Daily Planet. And you’ve probably even driven past the unassuming house on Glenville’s Kimberly Avenue, with the verdant front lawn and commemorative plaques on the fence, marking where Siegel grew up.

Even for someone like me, who has two Superman posters hanging in my living room, that just about covers it. After 80 years, Superman’s identity seems cast in steel. He does not grow or change or fail. He is immune even to death. He is stuck perpetually at the end of the hero’s journey.

Familiarity is his strength, and his cultural kryptonite. In a moment when every presidential tweet prompts, by design, fresh avalanches of outrage, The Atlantic asks “Is Democracy Dying” and the American way seems to be division and anger, could an octogenarian Boy Scout in tights have anything interesting to say?

In times of crisis, people gravitate toward Superman’s foil Batman, says Brad Ricca, Case Western Reserve University lecturer and author of the Siegel and Shuster biography Super Boys. Superman’s popularity dips when we need him most. Even an unscientific Google Trends comparison shows Batman has been more than twice as popular as the Man of Steel in searches over the last 12 months. Fear, Batman’s grisly instrument, resonates louder now than hope.

“Superman is more relevant,” Ricca says. “But we’re not listening to him.”

That’s why I traveled to Cartoon Crossroads Columbus to meet Brian Michael Bendis, one of the highest-profile writers in the world of comics. If you don’t know his name, you doubtlessly recognize the native Clevelander’s works. Over a professional career spanning almost 30 years, he has created iconic characters, such as reluctant superhero turned private eye Jessica Jones and the new Spider-Man, Miles Morales, star of an animated film out Dec. 14.

Bendis has written for Marvel Comics for most of his career. But last November, in a much-publicized move, he left for DC Comics. As part of the deal, Bendis could choose to write virtually any character he wanted.

Most expected him to select the moody, of-the-times Batman. But Bendis decided on Superman, the cheery hometown hero during his 80th anniversary year, at a time when his governing ideals of truth, justice and the American way are being questioned anew.

“These things are under siege,” Bendis told The New York Times, for a story about taking on the character. “This is the world we live in. These are not absolute things anymore. These are things worth fighting for.”

As Bendis emerges onstage at the Columbus College of Art and Design, the auditorium full of comics industry types — writers, cartoonists and art school students — cheer for him at full-bore. At 51, he wears a leather coat and jeans, and relishes the opportunity to crack jokes about his bald head.

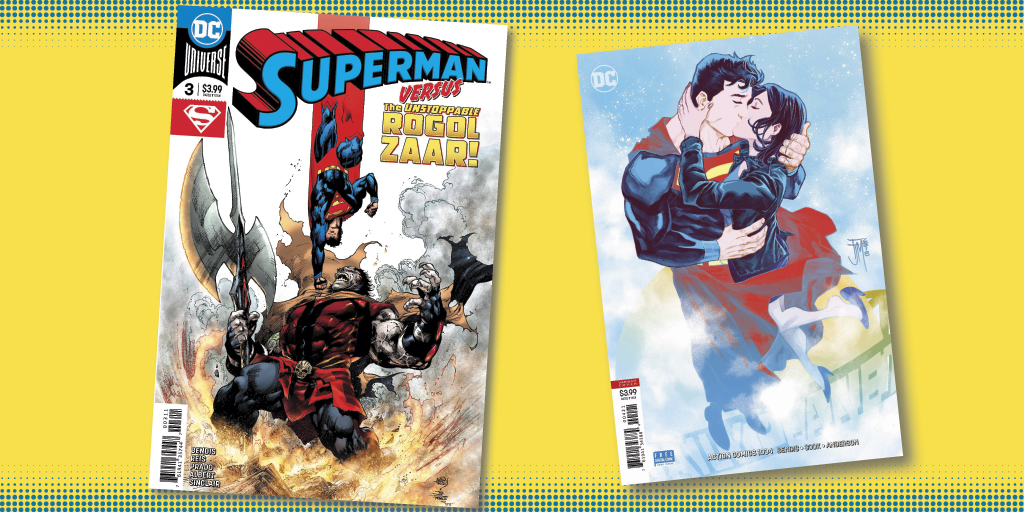

Bendis spends most of the evening dancing around Superman, offering little about the tensions in his ongoing storylines in Superman and Action Comics, or the miniseries Man of Steel, which ended in July. But later, during a question and answer session, he unmasks a little narrative trick that reveals a lot about where Superman might be headed.

“You take your character and you put them in the place they least want to be,” Bendis says. “What is the scariest thing you could do to that character?”

* * *

A week or so after Cartoon Crossroads, I call Bendis in Portland, Oregon, where he lives with his wife, four children, two dogs and a saltwater tank teeming with clownfish.

He is winding down from a whirlwind schedule of signings and panels at New York Comic Con. But Superman is on his mind; he has to write a script that night.

When some of his closest friends, fellow comic book writers, heard he was going to write Superman, they were confused, Bendis tells me. Superman seems so distant, so powerful. “They’d say, ‘Is there anything to relate to?’ ” he says. “And I’m like, ‘What?’ ”

Previous Superman writers such as Dan Jurgens, Bendis says, have honed Superman’s everyman sensibility. In the early parts of the six-issue Man of Steel miniseries, Bendis draws on that legacy. Superman’s life is surprisingly normal. Clark and Lois Lane are married, a holdover from Jurgens. They toil away at their Daily Planet jobs and have a preteen son, Jonathan. Superman spends his time defeating oddball, workaday villains like the Toyman. Jor-El, Superman’s biological father, is even alive.

But Bendis has been slowly yanking up Superman’s anchors. He places the Man of Steel in situations that test everything he holds dear: his family relationships, his Kryptonian origin story, his mission as Superman and his day job at the Daily Planet.

Superman’s happy world is skidding toward uncertainty. He is, like so many of us, being shoved out to sea.

“What this character wants is to save everyone, to make the world good for everyone,” says Glen Weldon, author of Superman: The Unauthorized Biography. “The only way you tell a halfway decent Superman story is to deny him what he wants.”

Bendis starts with Superman’s family. In the culminating scene of Man of Steel, Jor-El materializes in the Kents’ kitchen in a spaceship. Jor-El wants to take Jonathan on an intergalactic jaunt to train as his “Kryptonian heir.” Lois wants to go along, leaving Clark heavy with loneliness. He clutches Jon’s toys, bereft. Jor-El’s dismissive parting words rattle in Superman’s ears. “I can raise my boy, father,” he tells Jor-El. “To do what?” Jor-El replies. “Put out fires in his baby clothes?”

Superman’s father seems to think of his mission to defend humanity, to save people, with disdain. In Jor-El’s eyes, Jon need not follow in Superman’s footsteps.

“The gift that was given to me was bringing back his father, a father he can’t relate to and a father that may actually be disappointed in what Clark has done so far,” says Bendis. “That is oooooh so relatable.”

Bendis doesn’t hesitate to shake Clark’s foundations at work too. In a manner ripped straight from the headlines, the Daily Planet is in trouble and in the hands of a new, anonymous owner.

Supposedly unflappable editor Perry White is fraying with worry when Clark finds him hunched despairingly over his desk. “I’m being slowly bled to death, Kent,” the bedraggled editor sighs.

Then, in Action Comics, Bendis also alters the dynamic for Lois and Clark. Lois returns to Earth from her trip with Jor-El without Jon. She has not told Superman, however, and holes up in a hotel to work on a tell-all book. One night, she goes out for a burger (no pickles) wearing a wig, presumably to hide from Superman’s all-seeing vision. Of course, he discovers her.

To top off an already-bubbling thematic stew, Bendis has created a new villain, Rogol Zaar, who claims Krypton was not actually destroyed in a natural disaster, as Superman believed. Instead, Zaar boasts that he blew up the planet in an act of genocidal terrorism and has come to Earth to finish the job — by killing Superman.

The plotlines toy with the idea of Superman’s importance to those around him, Bendis tells me. People pay Superman and his ideals little attention. They belittle him and his mission, go off in pursuit of their own path or seek to destroy him solely on the basis of his race. He is present, but not truly recognized. He must fight for relevance.

“People [are] kind of asking Clark the question: ‘Are you doing enough?’ ” Bendis says. “Whatever our world is, you can’t help but look and go, ‘Am I doing the most with what I have?’ ”