People's Budget on the Ballot: Inside Cleveland's Push for Participatory Budgeting

by Annie Nickoloff | Sep. 19, 2023 | 1:24 PM

Anna Kim, Annie Nickoloff

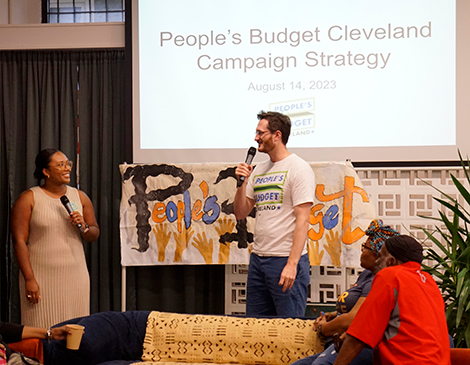

The people behind Cleveland’s possible People’s Budget gather, in August, to plan.

Some arrive already wearing their green-and-blue “People’s Budget” T-shirts; others wear matching stickers. They take pamphlets, they chat, and they sit on ThirdSpace Action Lab’s handful of couches and chairs and wait to hear more about what comes next.

A vote is approaching. This, Issue 38, is one of a few items on Cleveland’s Nov. 7 ballot, joining statewide issues like abortion access and marijuana legalization. PB CLE’s proposed amendment to Cleveland’s constitution would bring about $14 million (equal to 2% of the city’s annual operating budget) to the new group’s control, using it for initiatives voted on by Cleveland residents.

Here at PB CLE’s kickoff event, there are less than 100 days to rally support, and it all starts in this room.

Folks are excited, buzzing.

This room of people had moved Cleveland once before, pushing to place this issue on the ballot. And they’re confident about moving the city again: this time, at the polls.

Organizer Molly Martin takes the microphone and tests it while standing in front of a homemade “People’s Budget” banner. She’s affable and at ease in front of the crew of volunteers, many of whom she knows by name. She amps up the crowd and receives applause after mentioning Issue 1’s failure just a week prior — and then she celebrates PB CLE’s own early win.

“In 45 days, you got 10,000 signatures and we qualified for the ballot without needing a cure period,” she says. “How amazing is that?”

The team cheers. Martin smiles.

“We have 87 more days,” she says. “It took a lot of grassroots power to get us here, and it’s going to take a lot of grassroots power for us to win in November.”

The PB Proposal

A people’s budget — participatory budgeting — isn’t a new concept.

The idea’s roots trace back to the late ’80s in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and it later caught on in parts of other countries including Spain, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Iceland and India. In the United States, PB has taken a few forms in cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, Boston, Grand Rapids, Seattle and more.

Cleveland’s PB push didn’t start until April 2021, when a grassroots group came together to address the city’s $512 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds. Initially pitched as a $5.5 million pilot program, City Council voted down the proposal in January. The group returned in May to collect signatures to put its idea on the ballot.

This time, it pushed for more money. This time, it aimed to pull that money from Cleveland’s budget.

Participatory budgeting looks different wherever it exists. Cleveland’s proposal asks for roughly $14 million; meanwhile, Los Angeles’ PB program gets $8.5 million, Seattle gets $30 million and Grand Rapids gets $2 million.

“I do think it is very much like a democratic experiment, and something that has to be adapted to the needs of the city,” Martin says, “which is why we’re really pushing for funding and the administration of the process so that it can be done equitably — that folks who get to participate in the process are folks that represent the neighborhoods we’re trying to touch.”

PB CLE’s budget would ramp up for a few years until it reached its ultimate multimillion-dollar pool. A steering committee would work to ensure funds are used for “equitable civic engagement, resident leadership development, and robust resident decision-making and deliberation,” according to PB CLE’s proposed charter amendment.

An administrative budget would cover elections operations and community engagement, and also a full-time position to lead the committee — plus $5,000 compensations for each of the remaining 10 committee members. Then, the rest of PB CLE’s budget would be for the people to decide.

Aleena Starks, a steering committee member, supports some of the ideas already proposed by community members. The list includes things like mental health units, after-school programs, parks and senior services, Starks says.

“This is a direct opportunity for people that are normally excluded from the electoral process to find a way in,” Starks says.

PB Opposition

Many members of Cleveland City Council, including president Blaine Griffin, oppose the effort. Griffin says that PB CLE would be a “shadow government” and that having politically inexperienced, unelected leaders in charge of budgeting could lead to corruption. He also says that accommodating PB would lead to budget cuts to other key Cleveland services.

“I also have concerns that the people who have more time and are from more affluent communities that have the ability to contribute to this kind of process will benefit, whereas people that are in the margins of society, and people who have to work two jobs and people that are not in the loop, don’t have an opportunity to participate,” he says. “It can lead to even more inequity.”

Martin pointed out sections of PB CLE’s proposed charter that touch on equitable engagement and funding allocations and also noted that, while the steering committee would have open applications, members would be appointed by City Council and the Mayor’s office. She sees collaboration between PB, the community, the mayor’s office and city council as crucial.

“There are lots of different tools in the democracy toolbox. PB is about creating new ways for people to have a say, where they’re voting on projects and not people,” Martin says. “A lot of people feel some mistrust in the government. This is a way to try and build that trust.”

Mayor Justin Bibb, who, at first, supported a pilot PB program funded by ARPA dollars, now opposes the current PB CLE proposal, which would instead use money from Cleveland’s budget. City council member Kris Harsh wrote a scathing editorial published in cleveland.com and The Plain Dealer where he says, “Participatory budgeting is a Trojan horse that hides the true intentions of its promoters — to guarantee themselves a paycheck on the public dime without having to justify their worth or be held accountable to the taxpayers.

In mid-September, Griffin proposed legislation that would enable City Council to spend taxpayer dollars to defeat local ballot initiatives such as the People's Budget. The legislation was pulled before council's meeting on Sept. 18, and local political leaders criticized the effort. "Legal or not, I do not support the use of taxpayer dollars to campaign for or against ballot issue campaigns," Bibb said in a statement.

Misinformation has shrouded PB CLE’s messaging, Starks says. “PB CLE has been really clear about the opportunities of this campaign and what we plan to do and the purpose of that,” she says. “Voters are apathetic enough, and don’t need any more misinformation guiding them around how to best advocate for their own communities.”

The Vision

At the PB CLE kickoff event, supporters strategize and share donation links with their circles of friends. In breakout groups, some plan get-togethers; others coordinate canvassing routes and call lists. A slideshow shares the team’s strategy, point by point: its road to hopeful victory.

Before the night winds down and the campaign kicks into high-gear, before folks, including many young people, start knocking on doors, before they head to the polls themselves, the organizers paint a vision for what they want PB CLE to do — what, in some ways, this room of people has already done.

“I get so excited about young people brought into this process because that means that they can grow up in a world where they’re getting involved in city government; and they’re getting involved in spaces where decisions about their lives are getting made; and their first experience with democracy is about having direct power on how those decisions get made,” Martin says. “That’s what People’s Budget is about.”

Annie Nickoloff

Annie Nickoloff is the senior editor of Cleveland Magazine. She has written for a variety of publications, including The Plain Dealer, Alternative Press Magazine, Belt Magazine, USA Today and Paste Magazine. She hosts a weekly indie radio show called Sunny Day on WRUW FM 91.1 Cleveland and enjoys frequenting Cleveland's music venues, hiking trails and pinball arcades.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5