What 24 Hours on an Amtrak Train Showed Us About the Future of Passenger Rail in Cleveland

by Annie Nickoloff | Jan. 27, 2023 | 1:36 PM

Ethan Bowman, Annie Nickoloff, Courtesy Amtrak, Christine Warner

Standing in Boston’s South Station, I check the screens at the end of our track for the 10th time, waiting for an update. The passengers next to me look nervous. The train is already 15 minutes late.

I’m here for work — for this train — for a story. If something goes screwy, so does the story.

On this outdoor platform, I start to get cold. I shove my hands into my coat pockets and wander over to a guy with a guitar strapped to his back. I ask him if he’s waiting for the Amtrak, too. We make small talk. He’s headed to Albany, New York. I’m headed to Chicago. He got a ticket for cheap. I did, too. I tell him about the story concept: 24 hours on an Amtrak train.

“24 hours,” he mumbles. “That won’t be hard to do on an Amtrak.” He looks back down at his phone.

The Lake Shore Limited line is, technically, just about 22 hours long. Weirdly, yes, I’m hoping we’ll run a couple of hours late, hitting some kind of delay on the 1,017 miles we’re about to travel, making it a true 24-hour experience.

An Amtrak employee waves us over to a different platform. We all move, a mini-stampede, hustling to the open doors. Some folks turn left, filtering into business class. I turn right, into the coach section (my ticket was $120), and snag a coveted window seat. I check the time, 1:05 p.m., make a note, start the clock.

This whole thing serves as an opportunity for me to get to know a bit more about Amtrak, our country’s national passenger rail system, in a moment of major transformation. Last November, President Joe Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law dedicated billions of dollars to Amtrak, marking its largest investment since its inception 50 years ago. Those funds mean more rides, better times, new destinations, faster trains and eco-friendly attitudes have entered the national conversation following a decades-long dwindle.

In Northeast Ohio, those funds could reshape the service’s meager offerings to the region. Amtrak and Ohio’s government have, over time, cut back sharply on the service to Cleveland, a city that was once a hub for intercity rail travel.

Nowadays, the Lake Shore Limited is one of two (two!) Amtrak lines that run through Cleveland, and only one of three that run through Ohio. Clevelanders get a double-whammy effect: Those two trains only arrive in overnight hours, typically between 3 and 6 a.m. daily.

Still, plenty of Northeast Ohioans make use of the trains, and more might soon line up for tickets. Proposals for Ohio’s Amtrak expansions include a massive undertaking, revisiting a previously planned line connecting Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton.

Travel in Ohio might soon make a shift from car-centric to transit-oriented.

Having not taken an Amtrak train, I wanted to better understand its dynamic and its existing service to Clevelanders. I’m no stranger to the city’s RTA system or to taking cheap-ticket Megabuses and Greyhounds to destinations. I’ve taken trains in other cities and countries on trips before. But not Amtrak.

So, in late November, just before Thanksgiving, I boarded one of the two lines that runs through Cleveland to check it out.

To be clear: This is one sliver of what Amtrak offers nationally and what it could soon offer locally. Long-distance trains are funded and operated differently than state-sponsored lines that measure less than 750 miles. Plus, faster locomotives make journeys quick and more convenient in other parts of the country.

But as an introduction to the world of Amtrak, the Lake Shore Limited felt like a good place to start.

Maybe I went a little overboard, I thought, sitting in my seat. After spending a couple of days in Boston with my pals Matt and Ellen, now I had just 22-ish hours, six states and 21 more stations — including that late-night stop in Cleveland — remaining. Once we arrived in Chicago, I’d meet up with friends Sarah and Claire, spend Thanksgiving with my partner, Mike, and his family, and then head home.

With me, I had two bags stuffed with enough clothes to get me through the week, along with notebooks, my laptop, headphones, toiletries and snacks. I’d downloaded a few shows and playlists; for the meme, I first queued up “Love Train” by the O’Jays. I was as prepared as I could be.

Admittedly, I was a little nervous (and not just because of occasional experiences with motion sickness). I was about to spend a full day on one train, specifically in coach, where mystery neighbors await, where two bathrooms are available for dozens of people in a car. This wasn’t one of those fancy overnight cabs with beds and private bathrooms and included meals. And I was alone.

A good omen: Initially, I'm seated by myself, with an empty seat next to me to stretch into.

A conductor checked my ticket, and scribbled “CHI” on a paper slip above my seat. Our train crept out of the station, slowly, into the afternoon sun.

First Impressions

Even in the coach section, Amtrak seats are spacious and recline further back than a plane or bus seat. In this older train model, things are generally clean (in the first few hours, anyway). Despite all the coming and going and shifting clientele of our train’s passenger base, folks are courteous — the one exception being a scraggly bearded man in a sweatsuit, who held a full-volume conversation for a good three hours in the back of the car (on speaker phone, to boot).

I watch a changing Massachusetts landscape out the window, viewing Boston’s city skyline and then admiring the straggling fall leaves in Worcester. A woman in a pantsuit in the seat across from me works studiously at a Rubik’s Cube. Most people tap their phones. A few nap, awkwardly lumped across multiple seats.

Our first series of slowdowns arrives in the first hour, causing us to arrive 90 minutes late to Springfield, Massachusetts. We’re held up by freighters using the same train tracks (the culprit in most of Amtrak’s major slowdowns, especially on its long-distance lines).

(Illustration by Ethan Bowman)

At Springfield, the car fills up. A woman named Connie sits next to me, on her way to visit her sister in Albany for Thanksgiving.

Connie offers to watch my bags so I could more easily maneuver the neighboring dining car for a bite to eat. There, I order a Diet Coke and a cold ham and cheese sandwich (meh) for dinner ($12, including a $2 tip). Hanging out in the cafe car, with just two other passengers, is uneventful. I eat my meal and head back to my seat, where I nod off for a few minutes in eastern New York.

Then, we reach Albany, which is where we stay for another 90 minutes. Workers explain that our train’s engine is being replaced but don't explain what is wrong. “We do apologize for this unnecessary delay” crackles repeatedly over the intercom system.

Neighbors groan. I’m secretly grateful. The 24-hour earmark is a sure thing now. But as the minutes tick by, I start to wonder how many more hours would be thrown in, too.

I take the chance to quickly brush my teeth in the tiny restroom, which, at this point in the journey, stinks. The toilet is badly clogged. Do people know how to flush?

Bathrooms aside, I pick up on a bigger negative to Amtrak travel: While trains are dependable, their schedules can be unpredictable. Stopping and pausing and creeping are all part of the journey; you can’t necessarily board a long-distance Amtrak expecting to get somewhere quickly. You just have to be along for the ride.

In 2021, the Lake Shore Limited ran on-time only 55.1% of the time, according to an Amtrak report. That’s worse off than other lines that use tracks owned by Amtrak, like those in the Northeastern United States (with 80% and higher on-time performance). But it’s still far better than the Capitol Limited (a line from Washington, D.C., through Cleveland, to Chicago), which ran on time only 28.7% of the time. In 2021, freight trains caused delays of almost 900,000 minutes for passengers, according to a report.

Freight-related delays are so bad that a bill, the Rail Passenger Fairness Act, was introduced to Congress in 2021. The bill would allow Amtrak to bring civil action to assert its preference over freight while sharing tracks.

So, yeah. Long-distance Amtraks aren’t a great mode of travel for time-sensitive journeys.

The Albany slowdown would have made another version of myself — a version who wasn’t working on a big story about a train with famously big delays — anxious. But all you can do in a situation like this is wait. And wait. And wait.

“Are we there yet?” can only be met with: “We’ll get there when we get there.”

Ahead was Buffalo, a city that had been hit with historic snowfall just days before the journey, accumulating more than 6 feet in parts of the city. I close my eyes, quieting those thoughts and images of a blustery nightmare, and remind myself that I have extra time before I need to be in Chicago. That the trip is the point. That we’ll get there when we get there.

Before long, we take off. Soon after that, snowflakes swirl outside. At a stop in Schenectady, New York, a thin blanket of snow surrounds the platform signage. The train lights dim. Conversations quiet.

The first third of the trip is done, and I’m comfy in my seat, using my puffy winter coat as a blanket, feeling sleepy, watching the wintry scene gleam outside as the train chugs along.

Despite the frightening weather ahead, I find myself nodding off, groggy and half-awake and watching the changing New York scenery for the next few stations. Each time the train slows and stops, I send a text to Mike to track the timing, and promptly go back to sleep.

I’m sure I’ll wake up when the train makes its stops — sure that I’ll be awake when we eventually arrive in Cleveland.

Asleep in Ohio

The train lurches to a halt and sunshine is pouring into the window. Oh no. A new passenger is seated next to me, apparently someone who boarded in western New York or Pennsylvania. No, no, no…

I yank my phone out of the seat pocket in front of me. It’s 7 a.m. Outside, I see familiar suburban sprawl — somewhere on the West Side, I think. The train is halted, slowed down by another freighter.

Google Maps reveals our location: Berea.

I missed Cleveland, and I missed it by half an hour.

How I managed to sleep so soundly for the past few hours, and through just two stops (Erie and Cleveland), is beyond me. The last thing I remember, from early, early this morning, is gazing out the window as snow fell in the surrounding landscape, especially in Buffalo, where we passed by mountainous snowdrifts.

I remember feeling, in those early-morning moments, unconcerned, cozy and, mostly, exhausted. I remember the train attendees tapping on sleeping guests who had to disembark instead of announcing arrivals over the intercom. How considerate, I think, frowning.

My last series of notes, texted to Mike for status updates, are on my phone:

Utica 11:30 p.m.

Syracuse 12:40 a.m.

Rochester 2:14 a.m.

Buffalo 3:37 a.m.

I type my next message:

Slept thru Cleveland 😭😭😭

I’m kicking myself over the fact that this whole story was centered around Cleveland and Amtrak and, when we reached Cleveland, I was peacefully snoozing, leaning against the window.

But when I checked out Cleveland’s Lakefront Station a few weeks later, I learned that I didn’t miss much.

Largely unchanged from when it opened in 1977, the building, located at 200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway, was bleak at 12:30 a.m. on a December Saturday night. Just two passengers walked into the station, carting in a few suitcases with them and waiting for their ride. Three vending machines sold snacks in the back of the room; one had its labels covered in duct tape, and another had a handwritten “out of order” sign taped to its front. Vintage Amtrak posters lined the otherwise drab walls.

It stood apart from the massive hubs in Chicago and Boston, full of travelers, eateries and shops, all built into their sleek metropolitan designs.

(Photo by Annie Nickoloff)

But even this used to be a more exciting place. A photo from Lakefront Station’s dedication, shared on an Amtrak history archive, features hundreds of smiling people in a room full of activity. And before that, some passenger rail companies operated in Terminal Tower, in the heart of downtown Cleveland. Back in the late 1800s and in much of the 1900s — the heyday of rail — the city was serviced by five railroads, bringing in between 50 and 60 trains every day, says Stu Nicholson, the executive director of All Aboard Ohio, a nonprofit passenger rail and public transit advocacy group.

“Terminal Tower in downtown Cleveland was a busy place,” Nicholson says. “Essentially look at all the points on a compass, and you could go in that direction.”

(Well, except North — Lake Erie. But you get the idea.)

Many factors went into Ohio’s passenger rail systems’ downward spiral, but the biggest culprit was, by far, personal vehicles. The nation’s development of interstate highways in the 1950s and a growing availability of cars made passenger rail less convenient and a bit more obsolete for travelers at the time.

But people still take Amtrak. On this early Monday morning, I’m surrounded by them.

In Berea, our train starts moving again, slowly, through the suburb and further west. I get out of my seat and head to the dining car, groggy, and get in line behind a mother and her two children. They giggle as the train turns, sending them into a lean against the wall next to the deli counter. I order a coffee and plop into a booth, unable to hide my grumpiness. I watch the scene change as we pull up to Elyria and a handful of passengers board. I take a few notes, doodle in my notebook and send an update to my coworkers.

I begin to wrap my mind around the big Amtrak problem for Northeast Ohioans: The only time Clevelanders can use this service is at the time of day when a human being is most likely to be asleep. It’s the biggest deterrent to actually taking passenger rail.

“The joke that one of our members came up with several years ago is that in order to ride Amtrak in Ohio, you have to be a vampire,” Nicholson says. “Yet, people do ride — and they ride in surprising numbers.”

In 2021, Cleveland saw the highest Amtrak ridership in Ohio, with 32,263 passengers boarding trains over the course of the year, according to an Amtrak report. Toledo came in second place with 28,045 passengers, and Cincinnati was third with 7,164. (In 2019, before the pandemic affected ridership, Cleveland saw 49,195 passengers, falling just behind Toledo’s 50,192 passengers.)

Cleveland’s passengers board overnight on either the Lake Shore Limited or Capitol Limited lines, which depart Lakefront Station during its nightly hours: midnight to 7 a.m. ... Woof.

“People should be able to base their decision on riding a train on the actuality of a train being there in the daytime. A morning train. A late morning train. An early afternoon, an afternoon and a night train,” Nicholson tells me. “It’s been shown that the more frequent service you have on any rail corridor, the more people will ride, because they’ve got more options.”

More options could soon be available for Ohioans. In 2021, Amtrak proposed its “Amtrak Connects US” vision, which includes proposals for 39 new routes, 25 enhanced routes and 160 new stops across the country. The plan claims to serve 20 million potential new riders. The Amtrak Connects US project places heavy emphasis on Ohio, proposing a 3C+D line to connect Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton. The corridor would initially offer three daily round trips that would take place in five and a half hours. (By car, with no stops, the same trip would take roughly four hours and 15 minutes.)

Notably, the line would restore service to Columbus and Dayton, which haven’t had Amtrak rail service since 1979. In Cleveland, the proposed plan would also add three daily round trips to Detroit and one daily round trip to New York City. A new station at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport has also been mentioned, along with additional connections to RTA and improvements to the existing Lakefront Station near Downtown.

“It makes sense to take existing infrastructure and improve it. It makes sense to find ways for people to travel that have less of a carbon footprint. It makes sense to give people who need to travel another way to travel,” says Marc Magliari, Amtrak’s senior media relations manager. “People want options.”

In many ways, the entire dynamic of moving around the state of Ohio — and other parts of the country — could soon change, if Amtrak’s vision comes to fruition. “We believe we’re at the start of a new era,” Magliari says.

The key word is “start.” Cleveland and the state of Ohio have a long way to go before any new service is determined, and after that, at least a few years before trains could hit new tracks.

On the federal level, funding for trains has long taken a backseat to cars. But that tide might change: President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Law, enacted in November 2021, is pumping an unprecedented $66 billion in funding for rail, with $22 billion specifically earmarked for Amtrak.

Meaning: Trains might soon make a big comeback not just in Ohio, but across the country.

As the caffeine kicks in, I start to feel a little less grumpy about the whole asleep-in-Cleveland situation. I watch familiar neighborhoods roll by. There’s Amherst, my hometown. Then, the boat-lined docks of Vermilion. In Sandusky, we zip across a thin, rocky isle, surrounded by Lake Erie's choppy water and bobbing ducks. We pull up to Toledo, a popular stop with dozens of comings and goings. My neighbor departs.

“I need a cigarette,” the guy in front of me mumbles, shoving a hat down over his gray curls before shuffling into the wintry air for a brisk break.

Our last Ohio stop: Bryan, 10:38 a.m.

Goodbye, Ohio. A few hours remain.

Stops and Starts

This isn’t the first time the state has been primed for an Amtrak expansion. About 13 years ago, Ohio was prepared to build the 3C+D corridor. Nicholson, at that time a public information officer for the Ohio Rail Development Commission, helped secure a $400 million federal grant to start the service by the end of 2012.

That never happened.

Ted Strickland, the last Democrat to serve as the state’s governor, supported the project, lauding the potential jobs and industrial progress it could bring. When he was succeeded by John Kasich in 2010, the new governor squashed the plans, believing the line would be too expensive with a $17 million annual subsidy required. Since the line wouldn’t be high-speed, Kasich worried it wouldn’t gain enough ridership compared to car travel. Even when an impact study opened up additional funds to push forward higher speed trains, the money was still largely forfeited. (Kasich has, in recent years, thrown support behind other high-speed rail proposals like the Hyperloop.)

So, the 3C+D line didn’t get built in 2012 as originally planned.

“It’s too bad,” Nicholson says, “because if we had, we wouldn’t even be talking about reviving service in the 3C+D corridor. We’d be talking about expanding it.”

That $400 million didn’t just go away. Those funds and funds from other states that dipped out of the initiative went to California, Michigan, New York and Illinois — states that approved their passenger rail expansions, according to Magliari.

Despite Ohio’s fraught recent history with Amtrak, advocates and the company are more hopeful this time around.

“It’s amazing what a whole lot of federal money on the table will do to help you gain support for this,” Nicholson says. “That’s the difference-maker.”

(Photo courtesy Christine Warner)

Yet, cost remains a sticking point. Initially, federal funding for operations starts at 90% for the first year, then steps down from there, leaving more of the tab to the state as time goes on, says Magliari.

Unlike the long-distance train that I took (which is fully federally funded), most of Ohio’s proposed improvements and expansions would consist of shorter, state-sponsored trips — meaning they’d require operating agreements with freight-owned tracks, along with buy-in from participating states to cover costs.

Those costs will be determined from the Federal Railroad Administration’s corridor identification and development program, which will accept proposals until late March. A 2022 Columbus Dispatch article estimates costs at $17 to $20 million annually, split between Amtrak and Ohio. (Some perspective: $78 million of Ohio taxpayer money was dedicated to transportation in 2020, through the state’s General Revenue Fund.)

Amtrak receives federal funds, but so do other modes of transportation, Magliari says.

“I think, hopefully, we’ve finally gotten past this idea that the roads are paid for with gas taxes when they’re not. Certainly, maintaining them isn’t, and in a lot of cases, building them isn’t, removing the snow from them isn’t, rebuilding them isn’t," Magliari says. “So the suggestion that Amtrak gets a subsidy and nothing else does, I think we’ve finally outgrown that argument.”

He adds: “There is a public good in enabling people to have mobility in this country and to do so in a way that makes business sense, policy sense and service sense. All of this is done in lots of parts of the country now, and more parts of the country soon.”

That being said, Amtrak’s not an organization that booms with earnings. While it’s technically a for-profit company, it exists somewhere between that and a government entity. The president appoints Amtrak’s board of directors, which is confirmed by the U.S. Senate. Though it’s not a public authority, the company is backed by the federal government, a majority stockholder.

Throw in President Biden — dubbed “Amtrak Joe” for his cheerleading attitude toward the service and history of ridership — and the Infrastructure Law’s timing comes into focus.

Where once Amtrak expansions might have existed as a partisan issue, now it might not be quite so black-and-white. Here in Ohio, the Amtrak expansion has already gained support on both party lines. Notably, it drew support from the Columbus Partnership and the Columbus Chamber of Commerce, which both see a potential boon for the state’s economy. Amtrak has also worked with many of the state’s Metropolitan Planning Organizations, where many leaders have supported the work, Magliari says.

Cleveland’s MPO, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, is leading the effort to get additional east-west service corridors recognized by applying for the Federal Railroad Administration's Corridor ID program.

"The new proposal for Amtrak has Cleveland as both an origin and a destination in and of itself, as opposed to service that goes through Cleveland,” says Grace Gallucci, NOACA's executive director. “It gives us economic opportunity that we didn’t have before. It really connects us to these other places and connects them to us in ways that haven’t been done probably for over a century.”

This past fall, a handful of Ohio mayors — including mayors of all four cities on the 3C+D line — wrote letters of intent to the FRA to press the issue. The letters, coordinated by the Ohio Mayor's Alliance, mark a collective effort to push governor Mike DeWine toward a decision.

Where does that decision lean? As it so often does, it will depend on money.

DeWine launched a feasibility study with the Ohio Rail Development Commission to assess the cost and efficacy of the 3C+D line last May. DeWine's press secretary Dan Tierney says travel times, costs and Amtrak's potential impact on Ohio's freight system are all considerations.

Any expanded service, station improvements or new routes depends on the study’s results. We should know those results, Nicholson says, by spring.

One Day on a Train

We enter Indiana: a state that I have spent years driving or taking intercity buses through, on my way to Chicago to visit Mike’s family. Bland, endless, rolling farmland and little to enjoy other than a few rest stops serving Hardee’s and gas station hot dogs. I know it’s unfair, but when I think of traveling through Indiana, I just think ugh.

Here, a pair of passengers board and break out their laptops, headphones on, focused on their screens. The train’s wifi is spotty but workable. It allows these two the opportunity to type away and me a bit of time to scroll through TikTok and Instagram.

Work, social media, even movie-watching: all things that you couldn’t (or shouldn’t) do while driving a car.

Another thing you couldn’t do while driving a car? Drink. I notice, on my walks to the dining car, a selection of reasonably priced alcoholic beverages on the menu.

Dreams of an Amtrak ride down to Columbus to catch a concert, sipping a spiked seltzer or two while en route, sound glorious.

I consider ordering a glass of wine but decide against it, still nervous about the possibility of motion sickness. Instead, I opt for a refill of my water bottle, for free, from a spigot near the restrooms.

We stop in Waterloo, Indiana, a tiny station in a rural area. A few folks roll their suitcases on board in the morning sunlight.

This city, along with the previous stop in Bryan, are both towns located far from airports. They’re also two towns not serviced by Greyhound or Megabus. (While mentioning Megabus, let’s also mention that the bus doesn’t even service Ohio anymore, having cut its stops in the state in 2020.)

Watching a few folks hurriedly hustle onto the train, I could see how people in tiny towns like Waterloo, with a population of just 2,000, could rely on Amtrak to get around. The same can be said for smaller and mid-sized cities like Elyria, Sandusky, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and Utica, New York.

Chicago is fast-approaching. We breeze through Indiana, reaching Elkhart around noon, then hit South Bend at 12:20 p.m. About an hour and a time zone change later, we reach the 24-hour mark of the trip somewhere in Indiana, at 12:05 p.m. Central Time (1:05 p.m. Eastern Standard).

My back hurts. By now, I’m avoiding our train car’s restroom, which has become increasingly filthy as the hours wear on. My hair is a mess, tied up in a bun. I spend much of the next hour dreaming of a long shower and a good nap.

But, I’m okay. Half an hour later, the sprawling Chicago skyline reveals itself in the distance. I gather my things, packing away my cell phone charger, headphones, water bottle and what’s left of my snacks. I text my friend Sarah, letting her know I’d be at the station soon.

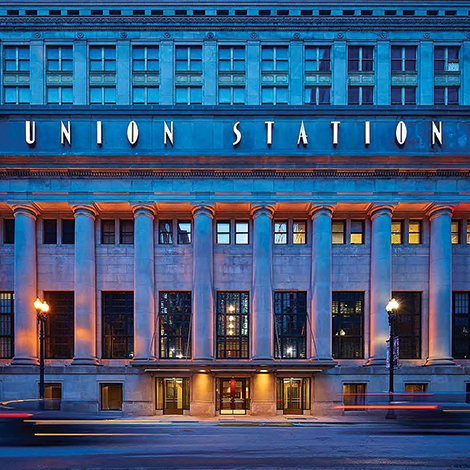

The skyline grows as we roll through neighborhoods, past Guaranteed Rate Field, approaching Union Station. We roll in.

The train slows with a screech, finally stopping at about 1:15 p.m. in the dark, busy belly of Union Station. It’s been 25 hours since we departed. We're three hours late.

Passengers shuffle off the train, an Amtrak worker warning us of the wet, slippery platform, helping us step down. A brisk walk down the platform and through Union Station helps stretch my legs. I hustle past queues of passengers lined up to board their journeys, then I step outside and get my first breath of fresh air in more than a day. Soon, Sarah swings by to pick me up in her car.

“How was it?” she asks, navigating the busy downtown streets.

“It was… good,” I respond.

This trip, which started as a weird story idea, also became a practice in slowing down. I allowed the journey to take as long as it needed to, paying attention to the people and moments around me.

Unlike what I’d predicted before the trip, I wasn’t the only person who took the Amtrak train from Boston to the end of the line in Chicago. One other passenger in the car also stayed on for the full ride, and a handful of other neighbors boarded for Chicago in western Massachusetts, experiencing more than 20 hours on the train. Most of the train’s employees also became familiar faces for the duration of the trip.

Taking the entire Lake Shore Limited line, start to finish, allowed me to see the swirling communities that formed and broke around me, a choppy sea of comings and goings, a microcosm of East Coast and Midwest travel.

There was the kind Amtrak worker who tried her best to answer every passenger’s question about every delay; there was the pair of friends donning eye masks and leaning on each other to sleep through much of the night; there was the college kid who shared, unprompted, that he’d been trying to get home to the snowed-in Buffalo for the past five days, and who finally reached his family that night.

It turns out that the stranger I met at the beginning of the trip was right: it’s not hard to spend a lot of time on an Amtrak train. For me, at least, that wasn’t so bad.

And it could get better, I think. It could get better.

Annie Nickoloff

Annie Nickoloff is the senior editor of Cleveland Magazine. She has written for a variety of publications, including The Plain Dealer, Alternative Press Magazine, Belt Magazine, USA Today and Paste Magazine. She hosts a weekly indie radio show called Sunny Day on WRUW FM 91.1 Cleveland and enjoys frequenting Cleveland's music venues, hiking trails and pinball arcades.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5