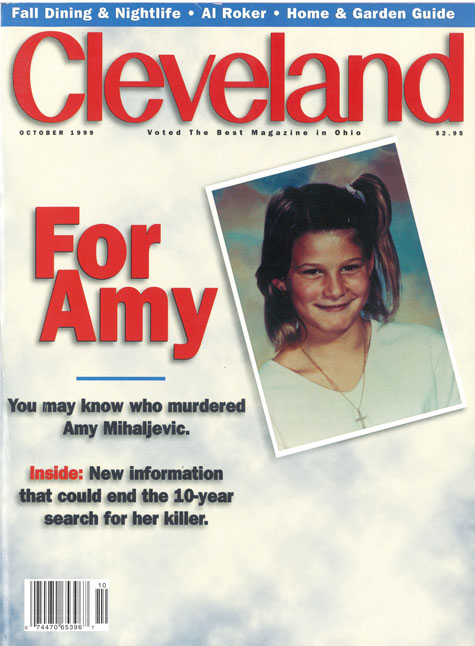

Who Killed Amy?

by Thomas Kelly | Feb. 5, 2020 | 1:00 PM

Steve Vaccariello

Editor's Note: This story, originally published in October 1999, is being republished as part of Cleveland Magazine's "Historic Read of the Week" series. Mihaljevic's body was found 30 years ago this week on Feb. 8. This month, a new podcast, 3News' "Amy Should Be 40," explores Mihaljevic's life and attempts to capture who the fifth grader was, not just her tragic end. In this story, published 10 years after Mihaljevic's death, the Bay Village police are opening the investigation up to the public in hopes of finding her killer.

It started as a brief but chilling flash of news, racing over the wire in terse words, spoken with careful reserve by news broadcaster, passed along in cautious tones from friend to neighbor.

Bay Village Police are seeking a little girl who failed to return home from school late this afternoon.

The words were cold but loaded, like a hand grenade.

Bulletins like these are often false alarms. Countless kids go traipsing off to school and come home just fine, day after day, year after year. A lot of them come home late. Between school and home for a 10-year-old is a world of wonder. She was off somewhere with schoolmates, stopped at a friend's, went to the store with her brother, came home and fell asleep in the guest room -- a few minutes, maybe, an hour or so, and the little mystery is solved, the girl is clasped in the arms of her exasperated but joyful mother and all is well.

Until that moment of relief, the throat-tightening thought that it may be something worse, the worst there is, claws at those who have heard a child is at risk. The first reports provoked no grave alarm. Bay village, after all, is one of the safest places on Earth.

Through late October, there were no murders in Bay Village that year. There were no rapes, no kidnappings or abductions in 1989; only three robberies, two assaults and 12 car thefts in the entire city. There had never been a child homicide in the city's history. The police are proficient. The citizens are responsible and community-minded. Bay Village is how modem civilization is supposed to be, tranquil and secure.

A follow-up news flash came quickly on the heels of the first.Still no sense of panic, but enough details to provoke a hint of real concern.

Ten-year-old Amy Renee Mihaljevic was reported missing by her mother late this afternoon. Bay Village police are searching the area surrounding her Lindford Drive home and Bay Square Shopping Center, where she was last seen at approximately 3 p.m., wearing a pale green sweatsuit with lavender trim. She is 4-foot-10, 90 pounds, with straight blonde hair and brown eyes.

3:14 p.m.

Amy's brother, Jason, then 13, had taken the first small step that

led to the most intense child search in local history. Jason had called

his mother at work to report Amy's absence when she was only minutes

late. Both kids were usually home by 3 p.m. and both called Mom at work soon

after just to say, "Hi, we're home." Every day. No special reason. There

had never been an incident, no cause for concern; it was just the family

way. The pattern was so consistent that Jason sounded the alarm within

minutes.

For Amy's mother, that call was the first raindrop of the violent thunderstorm that would wreak havoc on her family and her life. Today, Margaret McNulty recalls that she was only mildly concerned. "She had mentioned something to me about trying out for the choral group," she recalls, "so I told Jason to call back in a little while. I told him not to worry."

But she did. "It was a feeling,"she says. "A very bad feeling. "After 10 years, that thought is enough to send a ripple of emotion across her face like a chill wind through the room.

3:30 p.m.

Jason called again. "Amy's still not home." Even knowing Amy had

reason to be late, Margaret was concerned enough to gather her things

and prepare to leave her work at Tradin' Times magazine to get home and

check on her little girl. But something happened, something not widely

known before, something that haunts Margaret to this day.

Amy called.

3:40 p.m.

To her mother's great relief, Amy

called and Margaret sat back down at her desk. Everything was fine. Or was

it? She asked how the tryout went and Amy said, "OK. " She asked how she

was doing and Amy said, "Fine." Margaret had the clear impression that Amy

was calling from home. They talked briefly, Mom and Amy, then bye-bye

and see you soon. It was the last time Margaret ever spoke to her

only daughter.

"That was critical," says Jim Tompkins, the lead detective on Case #BV-8900713 from the first day in 1989 until his retirement this past January. "It bought him an hour or more." Precious getaway time for the man authorities call the "Unknown Male."

Expert analysts also believe this crucial event reveals important details about him. They are certain he was standing right there, that he knew Amy was supposed to call and told her what to say. "It tells us he was executing a bold plot that included Amy, her family and the police — Bay Village PD headquarters is right across the street from that mall, " says Robert Ressler, a pioneer in criminal psychological profiling for the FBI." This is an intelligent man, presentable, well-spoken. This is a complicated personal crime."

Margaret went back to her work with the inexplicable but nagging feeling that things still weren't right. "She answered my questions with a word — 'Yes,' 'OK,' 'Fine' — that wasn't like her," says Margaret. "She was a little chitter-chatterbox." A short time later, for reasons known only to a mother, Margaret left work early and rushed home. She wasn't in the house half a minute when Jason said, "Mom, she's still not here."

4:30 p.m.

Margaret ran

back to the car and drove to Bay Middle School. The building was closed, no

cars in the lot, no one there, only Amy's aqua-colored bicycle with the

white wicker basket, alone and abandoned at the rack. For Margaret, that

riderless bike was an instant and unshakable symbol of doom. She fights

the tears while trying to describe what was, for her, the defining moment of

tragedy. "I knew right then it was something terrible ... disaster," she

recalls. "I never said it, but that bike — I was sick, I was shaking, I

knew something terrible had happened to Amy."

Margaret drove directly to the Bay Village Police Department, part of the City Hall Building at Wolf and Dover Center roads, and ran inside. Two officers huddled with her right away, sat her down and got her story. They took notes, asked questions. It had been less than an hour since Amy had called. It would have been understandable if the Bay police advised patrolling officers to keep an eye out for her and let it go at that. In spite of the lack of any evidence of foul play, that's not what happened. The case officer picked up on Margaret's instinct wavelength. "Yes, [officer] Barbara Slepecky made the assessment on the spot," recalls Farrell Cleary, Bay Village safety director. "It was her call and she immediately classified it as a child abduction. So we went full bore on it right away."

5:14

p.m.

The first police bulletin provided a full description of Amy to police on

duty, quickly relayed to their counterparts in Westlake, Rocky River,

Fairview Park and Avon Lake.

6 p.m.

Mark Mihaljevic

arrived home from a day on the road as a customer service representative for General Motors, unaware of anything amiss until he walked in the door.

Shocked silent at the news, he did the only thing he could — roll up his

sleeves and pitch in.

Mihaijevic has a humble but solid presence, like an honest farmer. He's not tall, but broad shouldered and thickset. He doesn't waste gestures or expressions. There aren't many lines on his patient face. He listens mostly; when he speaks, he measures his words.

"They told me she was just ... missing. The police were there, and I went all over the house with them from top to bottom." Friends of the family soon joined him and "... we just wanted to do something," says Mark. "We searched the ravine, the one that runs through to the lake. We walked the whole thing, every inch, calling her name, Amy ... Amy."

7 p.m.

Before the last light left the sky, a

massive search was on. With a swiftness of purpose that earns a city the right

to be called a village, countless volunteers joined authorities to scour

the area and network with other friends or neighbors who might have seen

Amy.

9 p.m.

The quiet suburban police station

had been transformed into a command post, with uniformed and

civilian employees flanked by an instant auxiliary of volunteers. Extra flashlights,

food and supplies flooded police headquarters. Calls poured in offering

more vehicles, boats to scan the lakefront, dogs to search the

woods.

At the Milialjevic home, Margaret was on the phone, as she had been for hours, calling everyone she could think of and answering everyone who called on the other line with the same negative mantra. "No, she's not.... No, we don't know.... No, nothing."

The night passed, that awful first night, the darkest night. The odds of successful recovery of an abducted child plummet rapidIy after the first six hours. For the hundreds of police and volunteers who scoured the darkness, every tick of the clock was like a hammer blow. Dawn came without promise: no sign of Amy, not a clue to her whereabouts.

Saturday, Oct. 28, 1989,

7:10 a.m.

Less than 14 hours after police first became aware

of Amy's absence, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was alerted (as kidnapping

is a federal offense). The FBI joined in while city and neighboring

police, Highway Patrol, Metropark rangers and most of Bay Village

continued looking frantically for Amy.

Special Agent Dick Wrenn has led the FBI investigation from the start. He is still the point man today, still intensely committed to solving the crime. Wrenn lives in Bay Village. He has children Amy's age. He shops at Bay Square.

A neighbor had called early that morning and told him the news. Wrenn and Tompkins began canvassing the neighborhood, speaking to residents. A neighbor of Amy's family gave the investigators troubling information from his daughter, a close friend of Amy's. Wrenn understood the implications immediately. It was the bombshell of the case.

The story, confirmed by Jason and other friends of Amy, changed everything. The girl had not been randomly abducted. She had received some phone calls, maybe several, from an unknown male. He knew her phone number and where she lived. He knew where her mother worked and what time she came home. He knew the neighborhood and the local strip mall. He befriended Amy on the phone, gained her blind trust and convinced her to meet him at Bay Square. Amy had leaked the "secret" to a few close friends: He was going to take her for a shopping spree at a bigger mall to select a gift for her mother to celebrate a promotion at work. He hinted at a bonus gift for Amy, just for helping out.

He was bold enough to lure Amy into a

preconceived scheme, startling in audacity and bone chilling in intent. He

was brazen enough to meet her in broad daylight, in full view of many

children and

adults, right across the street from the police station. He was cunning

enough to pull it off. Whatever he said, however he acted, it was

beguiling enough that Amy strolled to his car without concern. This was not

some mentally deficient deviate, seized by temptation, committing an impulsive

crime. This was a creature who took his time, crafted a plan and savored

the details of atrocity.

In many cases like this, there is nothing to go on, not a shred of information beyond the frantic report of a child who vanished.This was an exception: Witnesses had provided a good timeline and a fair description of a suspect seen approaching Amy. Fliers with Amy's picture were in hundreds of locations before noon. By sundown, the count was in the thousands, spanning hundreds of miles and three states. Family members, neighbors, friends and remotely possible suspects on police lists had been questioned before the day was out, some two and three times. Forensic specialists were on hand, searching for minute clues. FBI profiler experts were called for analysis. Countless Bay residents abandoned all else to help find Amy.

Saturday night, as the people of Bay Village continued to mobilize in large numbers and expand the search, FBI agents were grim. Led by Wrenn and his partner, Special Agent Gary Belluomini, they had more than 60 agents on the case already, but they knew the numbers all too well. "With Amy gone 24 hours, and the setup story with the stranger," says Wrenn, "we knew if we didn't find her quick ... it was clear we were dealing with a crisis situation."

Still, no one faltered. No one stopped looking. No one gave up. It became the most intense search for a child in local history, involving every conceivable law enforcement agency and an army of volunteers. Federal, state, county and local law enforcement personnel have logged more than 60,000 official hours and thousands more off the clock. Hundreds of promising tips have been tracked down and dismissed,14,000 people interviewed, 120 potential suspects investigated and questioned intensely, 8,000 leads pursued and abandoned. The story and pictures were featured in major newspapers and on national TV shows like "America's Most Wanted" and "Unsolved Mysteries." Two million copies of the Amy poster were distributed, in all 50 states and from Europe to Australia.

The community effort was so vast that someone had to take charge and longtime Bay resident Howard Kimball stepped forward to do just that. He emerged as gentle commander of the volunteer army, manning the communications center on the top floor of City Hall. The contributions of time, food, money, assistance and services from regular citizens who cared enough to get involved cannot be counted.

"I can't give you any names, because there were so many, and I don't want to omit anyone," says Kimball. "A printing company donated all the print work and insisted we never mention their name. The airlines, the TV stations, restaurants — you know, we asked for paper, and so much came in one day, we had to move it to the fire station. People were so good, so amazing." No one was concerned with keeping a tally. Their only goal was the safe return of Amy to her family. "It was devastating, how it turned out, but I'd do it all again in a minute, " says Kimball. "We all would."

The heroic effort of Amy's Army ended in a desolate field near Ruggles Township in Ashland County on the dreary gray morning of Feb. 8, 1990. Janet Seabold was jogging alongside a silent stretch of County Road 1181 when she stopped in her tracks at the sight of a small figure clad in a pale green sweatsuit laying face down in the weeds. She sprinted a quarter mile to the nearest farm house and banged on the door. Ashland County sheriffs responded to a 9-1-1 call at 7:30 a.m. Like every department in the region, they had been on notice for months of the possibility of this worst-case scenario and they knew exactly what to do. They blocked the road, secured the scene and called the FBI.

"We went to the Mihaljevic house as soon as we had official confirmation," says Wrenn. "Jim Tompkins and I, with [Bay Village Police] Chief Garreau and [the Rev.] Tom Madden from Bay Presbyterian. It was a horrible thing to have to do. ... The media was already there." The fear that had tormented family, friends and investigators turned to loss. The Unknown Male who took Amy had taken her life.

Cuyahoga County Coroner Elizabeth Balraj determined the dreadful facts, with more details filled in from subsequent examination by FBI scientists. Amy had been deceased for some time. Most likely, the murder had occurred shortly after her abduction, probably a few days or less. She was not killed immediately: Amy had eaten at least one meal after she was taken, maybe more. Her death was brutal but quick. She had been forcefully struck on the head, then stabbed twice in the neck.

The search for Amy Mihaljevic had ended in tragedy. The search for the murderous Unknown Male was only beginning.

This Oct. 27, it will be a full decade since the crime. In one of the most frustrating cases ever for many involved, no arrests have been made. The questions echo down a 10-year corridor. Who is he? Where is he? Why can't we find him? Is he is still here, masked as one of us, going to his job, socializing with friends and family? Why did he do it? Why Amy? What else has he done? What else will he do?

Recently, the principal investigators from 10 years ago joined currently assigned agents and officers to discuss the case that they take as hard as if Amy was their own.

Dick Wrenn is there. The FBI agent is still on the case. He has never set it aside. He speaks of it with such intensity, it might as well have happened last week. "This was a crime against children, against family and community, " he says. "We're not going to let it go. We're determined to catch him."

Bay Village detective Jim Tompkins recently retired from the force, but not from the case. "You know, I could have seen the whole thing come down if I was looking out my window," he recalls. "Hardly a day goes by when I don't think about that. I'd do anything they ask me."

Special Agent Gary Belluomini, retired after 32 years with the FBI, cannot put the case behind him either. "It was 17-18 hours a day, seven days a week," he says. "We had tons of leads and some sounded so good, but we had to condition ourselves against that." The veteran agent admits the case took its toll, mentally and physically. "It was an emotional rollercoaster. It was draining. We wanted this guy so bad."

Lt. Mark Spaetzel is the lead detective today. He looks too young to have been on the force in 1989, but he was a patrolman, giving a public service speech to a Bay Middle School class the day Amy was lost. He didn't realize it until much later, but Amy was in the class. "It's a very active case," he affirms. "We still get five or six calls a month."

Bay Village Mayor Tom Jelepis provides his own office for the meeting. Safety director Farrell Cleary joins the group and seems to speak for the entire city when he declares, "For 105 days we focused, we looked to recover Amy. From that day [that she was found], we started looking for Amy's killer and we haven't stopped. And we won't stop."

Later, this group is supplemented by a two-man delegation from the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va. Stephen Etter is supervisory special agent for the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime. Wayne Lord is a supervisory special agent with the Critical Incident Response Group: Child Abduction and Serial Killer Unit. These are the formal names of the fabled FBI "Profiler Units," now a generation advanced from the criminal behavior analysis group made famous in TV shows and films such as "Silence of the Lambs." Lord and Etter are part of the most sophisticated criminology team in existence, composed of experts in diverse scientific disciplines who collaborate on determining factual and theoretical attributes of unknown violent criminals.

Lord speaks of "predator tendencies" and "territories." His background in zoology became the basis for his expertise in human predators. His doctorate is in entomology, the scientific study of insects. With crime scenes, bodies and other physical evidence, the study of the condition and activity of minute life forms at a microscopic level yields a wealth of information — timelines, locations, aberrations.

Etter emphasizes logistics, motives and M.O.'s (modus operandi). With advanced degrees in business, his methodical approach is enhanced by 10 years of intense analysis of the psychology of violent offenders. He follows the subtle trail of "conscious and unconscious choices made" in search of patterns of behavior that help define appearance, demeanor and lifestyle.

Lord and Etter have come to Cleveland specifically to provide the recently completed analysis of the case, rare public disclosure for the FBI in an ongoing homicide investigation. Wrenn explains, "I've never been involved in a debriefing of a reporter to this extent in 27 years. But at this point, we're all willing to do it because we think it might help."

These experts tell the whole story, including a summary status of the case: Of the thousands of potential suspects ever to appear on the radar screen, less than two dozen remained priorities after acute investigating. However, investigators continually review a comprehensive list of previously investigated subjects.

Some rumors persist that one of two men on that list may have been the killer, but investigators are virtually unanimous in the certainty that neither one was involved. Suspect No. 1 was a troubled young man from Fairview Park who joined the Volunteers for Amy early on. He was questioned several times, his story checked and double checked. He was found to have serious personal problems, medical and emotional, unrelated to the case. Months after Amy's disappearance, he consumed a lethal amount of ethanol — "dry gas" — and died three days later.

One veteran FBI agent briefly involved in the case had questioned this suspect personally and maintained a "gut feeling" that he was hiding something. He later cited the suicide as a possible indication of guilt and named the man publicly as a good candidate for the Unknown Male. All other investigators insist he was not the one.

"After his death, we had access to his home and belongings," Wrenn recalls, "and there wasn't a shred of evidence [for] this or any other crime." Etter adds that "...he simply didn't have the capacity to commit this type of crime."

Suspect No. 2 worked at the stable where Amy went horseback riding on weekends. His appearance was vaguely similar to the known description, and a background check had focused serious attention on him for months. Intense surveillance and exhaustive investigation yielded nothing. "He didn't do it," says Wrenn. "I'm as certain as I can be in an uncertain world."

"Of all the suspects," says JimTompkins, "20 to 25 were most interesting, but we never had a sense of, 'Yeah, this is the guy.'" Authorities believe the Unknown Male is still out there, waiting to be caught.

The rest of this story is written for one reader — the one who has that last fragment that will break this case and close the Amy Mihaljevic tragedy. All the experts and authorities are confident that that person is out there, that he or she may well be reading this, and that one conversation with him or her could end it all.

Maybe it's you.

If it is, you probably have no idea that you hold the key that has been missing for 10 years. You didn't do anything wrong, you didn't participate in any crime, you haven't been part of any cover-up. Maybe you didn't even know Amy or her family, or anyone who did. Still, you could have that incidental piece of information that investigators know is the Rosetta stone of the Amy Mihaljevic case.

For the first time, FBI and police have agreed to release details kept confidential for a decade. It is typical in a case like this for certain facts to be withheld, kept in reserve to separate the wheat of truth from the chaff of dead-end leads and false confessions. But now, with so much time passed, investigators believe it may be beneficial to divulge additional data in the hope that one reader could make one remote connection.

First are the objects, the things Amy carried. Never previously disclosed, they are innocuous and insignificant by themselves, but they could crack this case wide open. Amy had these things with her when she was taken. After all the years of searching, none have ever been found. Some are rare enough to be memorable and unique enough to be clearly identifiable. Maybe they were burned or buried to cover the tracks of the Unknown Male, but it is not unusual for this kind of criminal to make the arrogant error of keeping a memento of his crime, a "trophy" of his success. If the Unknown Male kept one or more of these objects, even for a short time, someone might have noticed.

The most distinctive is a pair of shoes. When her body was found, Amy was dressed exactly as she had been when she disappeared in October, but forensic investigation has confirmed that she was not simply seized and slain. She had eaten again, after she was taken, at least once. The experts are certain that her clothes had been removed, then put back on her body after her death — all except her shoes and her earrings.

Why? "Because this was a sex crime," says Lord. "We know that with virtual certainty. Amy was a targeted victim, specifically selected by this man with criminal sexual intent, and there are clear patterns of behavior subsequent to a sex crime like this."

Lord goes on to describe FBI theories of the missing items. "We see enough cases where the offender keeps items from the victim, sometimes gives them as a gift to someone else." The shoes were uncommon: black leather ankle boots with vertical rows of silvery studs, bloused at the ankle. The Unknown Male could have had a problem getting them back on her feet, then tossed them in a trash can many miles from the scene. But he may have been too obsessed with the shoes to part with them so quickly.

The earrings are even more likely "souvenir" items. "They are particularly important," says Etter. "Just the kind of things the offender might give to another female." They were "tiny blue turquoise silhouettes of a horse's head," according to Amy's mother, "mounted on gold metallic studs." Amy's favorites.

Amy also had her school backpack, a fairly common blue denim design with red piping and black plastic buckles, and a plain, white nylon windbreaker. Neither one is unusual for a fifth grader, but it would be odd for a grown man with no children to have one in his home or car.

The last item is exceptional. Amy's dad had given her a sleek, black leather folder with a brass clasp emblazoned with the Buick three-chevron logo and the legend, "Best In Class." An award item from the GM sales catalog, there are relatively few like it and it is unlikely one would circulate far beyond the realm of Buick dealers or GM sales or service staff.

Did you ever see any of these things where they didn't belong? Did it ever catch your attention that a grown man had one or more of them for no apparent reason? Did anyone ever mention them or show them to you?

The last piece of new information is the revised profile of the Unknown Male, provided by the best criminal analysts working today and based on all available information from the case itself and years of comprehensive data compiled, computerized and cross-referenced at the nation's most advanced center for the study of criminology.

Presented here, for the first time, is the closest description of the Unknown Male — what he looks like, what he does, how he behaves, where he lives. Obviously, because his identity remains unknown, these are theories, not facts, but if recent history is any indication, when he is finally caught, he will be remarkably close to much of the description provided by FBI experts. One crucial aspect of the revised "profile" relates to the ubiquitous poster of the suspect. Remember the undistinguished drawing of the slightly built man, unremarkable in appearance? Forget it. At least for now, set it aside. It could be that the Poster Man is not an accurate portrayal of the Unknown Male. The description provided by witnesses was based on fleeting glimpses of a man seen approaching Amy, but not in actual contact with her. There was no reason to scrutinize him and nothing extraordinary about his actions or appearance. Wrenn emphasizes that "people should not hesitate to contact us if they have some information, but the man doesn't look like the drawing — I can't say that strongly enough."

The rest is a behavioral composite based on 10 years of available information. The offender is a white male. At the time of the crime, he was in his mid- to late 30s, older than average for a first-time child aggressor. He is not remarkable in appearance, within average ranges of height, weight and build. He may look presentable, but not accomplished or professional. "He is socially marginalized, " according to Etter. "Not in the mainstream, not a run-of-the-mill citizen."

"He won't fit in with his peers very well, especially women," adds Lord, "and the people who know him will describe him as 'odd' or 'difficult.' It's likely that he was living alone, with a single roommate, or maybe still at his parents' house." It is most unlikely he was in a successful marriage, with a normal home and family life.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the report is that the killer was most likely to have undergone some sort of dramatic change in his behavior, personality or appearance in the weeks preceding the crime. He developed a sudden compulsive or obsessive disorder, experienced a personal catastrophe or an emotional setback. "He may have started drinking heavily, or stopped drinking suddenly," says Wrenn. "He could have started into hard drugs or quit a drug habit." There was a drastic change in his life, maybe a sudden fascination with a cult or radical religious group. Something happened to this man in the fall of 1989, something that would have been noticeable to close friends or relatives. "There was a pre-event stressor," says Lord, "something that took him from fantasy to action."

The stress in his life may have been reflected in a dramatic change in his physical appearance. He let his hair grow long or cut it very short. His health suffered. His weight fluctuated. There were changes in his appearance or lifestyle.

In addition, one important logistical aspect should be noted. This man was not passing through. Contrary to the family's trusting conviction that no one known to any of them was involved, authorities are confident that the Unknown Male has "... reason to know this area," according to Etter; "A resident, a contract worker or delivery person familiar with Bay Square." Lord cites the need for such a predator to select a "hunting ground where he can ... move comfortably through the tall grass."

Lord explains that the Ashland County location is just as important. "This was not random," he says. "When you are disposing of something that could ruin your entire life, you're going to be careful." The Unknown Male knew County Road 1181. He had been on that lonely stretch of asphalt before. He knew he could quickly place Amy's body just over a shallow ridge a few yards from the pavement and expect it would go undiscovered for weeks or months. Wrenn confirms the conclusion: "Yes, we think he was familiar with Bay Village and familiar with the area in Ashland."

The experts go another step. "We believe he had knowledge of the family," says Etter, "personal knowledge in considerable detail."

The most disturbing part of the

report concerns his behavior since the crime. Because there has not been a

similar crime reported — at least nothing like the complicated telephone plot to lure Amy to a deadly rendezvous — the general perception is that, to the best of the investigators' knowledge, the Unknown Male has never claimed another victim.

"We don't know that he hasn't done this again," says Etter. "He may have left the area and done something far away, or he may have changed his M.O." Etter goes on to explain the difference between an M.O. and the signature of a criminal. "An M.O. is just what works, and it can vary," he notes. "The signature aspects of a crime do not vary — they are fundamental." Because of the single known crime and limited evidence, there is no known signature in Amy's case. The unique M.O. — the phone-call setup — may have evolved to a different tactic.

The best hope experts cite for new information is from past victims, and they believe there may have been some who have never spoken up. "If you look at the statistics," says Etter, "it is likely this person had criminal sexual contact with other female children and some of those acts may not yet have been reported."

"Many women are hesitant to report sexual assaults for a variety fo reasons," adds Lord. "It could well be that this offender made other attempts that did not end in death." Information from a past victim would be of paramount interest to investigators.

"You may have good recall of what he looked like, his vehicle, where he went —things that deceased victims cannot tell us," says Lord. He adds that through forensic study, "...Amy tried to tell us a lot. Now someone else has to help, add just a little more. That's what we need." Etter provides a startling statistic: "In 70 percent of cases, there are unknowing witnesses that have valuable information they never thought to bring to light."

Is it you? Are you that unknowing witness?

It has been 10 years now, and life goes on. Jason Mihaljevic, Amy's brother, recently graduated from Kent State University. He was married this past June and plans a career helping children in rural areas.

Mark and Margaret Mihaljevic divorced less than two years after Amy's death. "Yes, it played a part," says Margaret. "It wasn't the only thing, but it made..." Her voice trails off and she looks away. "It was hard on us both. We're friends. It's all right." Mark nods, unspeaking, and squeezes her arm. In a large conference room with a dozen chairs, they choose to sit side by side, pulling their chairs close. Mark remarried years later. Margaret has remained single.

Amy is buried near Mark's parents at the Mihaljevic family plot in Milwaukee. There is a simple memorial on the grounds at Bay Village City Hall, purchased through a fund-raiser led by longtime local radio host Bill Randle as a tribute to the little girl who meant so much to so many. "I visit it often," says Margaret. "To this day, people still leave flowers and notes and stuffed animals. She loved her stuffed animals."

Is there any saving grace? Did anything good come of this tragedy? For the only time, Mark Mihaljevic speaks at some length. "Yes. It brought together a whole community. ... You know, before noon on Saturday — it hadn't been a day yet — the Buick dealers I work with put up a big reward," he says. "Everyone — the sense of community was so massive, the food, the money, the people." He has to stop for a moment. "It was overwhelming."

Margaret pats him on the hand, then ads a thought of her own. "A lot more parents became aware of how fragile their children are," she says. "You think you live in some suburban bubble, but evil has a way of happening. There are cruel people out there. Harsh people.

"It still hurts, it's very painful, but I'm not the only one hurting. It affected so many. ... Do you know there were people, volunteers, who had never met Amy, but they were so involved that, after, they needed counseling, too?

"Why Amy? Why us? Why?" she asks of no one. "There isn't any answer. And I've come to terms with the fact that there is no answer. ... All I would ask is if anyone has an inkling or suspicion, a little tiny doubt — please let the authorities know. It's not for punishment. It's that this man is still out there, a terrible risk to children. ... Please come forward. One little piece of information — the police and the FBI have a lot of threads, they just need one thing to tie them all together."

Maybe you know something. Maybe you saw something — one of the items pictured here. Maybe you heard something. There is a substantial reward offered, yes — $10,000 from the FBI — but there's much more to be claimed by the good citizen who steps forwards: closure for a family, solace to a community, relief to parents, resolution for investigators, peace for Amy. "Just one thing," says Amy's mother.

Maybe you have it. If you think you do, call the FBI at 216-522-1400 or the Bay Village police at 440-871-1234 and put this story to an end.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5