On a clear Tuesday morning, the Motor Vessel Mark W. Barker slides away from the Cleveland Bulk Terminal near Whiskey Island and works toward the mouth of the Cuyahoga River.

We are stationed in the spacious captain’s deck, positioned near the ship’s stern and four flights of stairs above the main, 639-foot-long deck. Surrounded by charts and logs, captain Alex Weber and wheelsman Zachry Filipiak have their eyes glued to the glistening path in front of the lengthy ship.

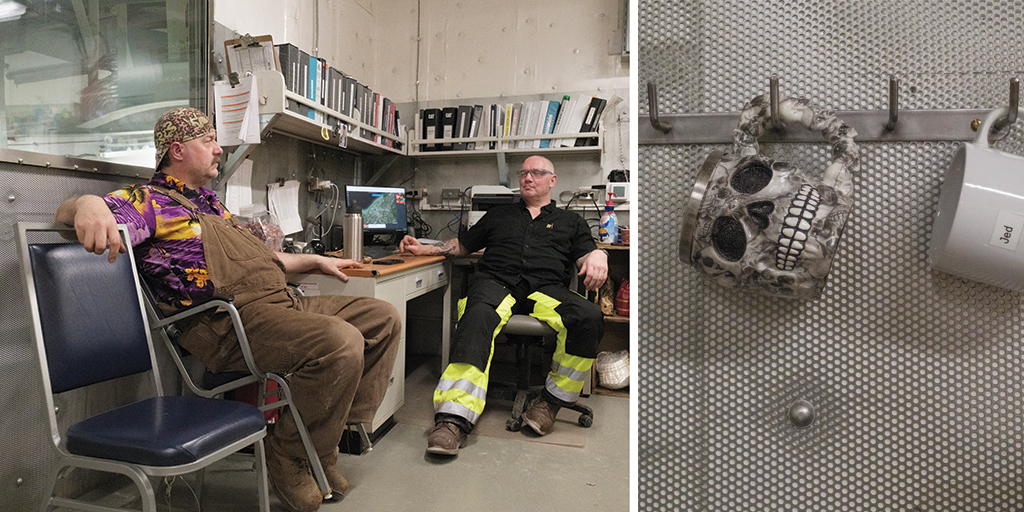

Here, the smell of fresh coffee drifts from a pot brewing in the corner, next to a bowl of candy and above a mini-fridge containing a tub of homemade pickled eggs that Filipiak and a friend made a few weeks ago. (He lets us know they’re there for the taking, in case we’re hungry.) Calming soft-rock tunes play lightly in the background; Toto and James Taylor and Uncle Kracker’s “Drift Away” — and, here, the song goes, “I wanna get lost in your rock ‘n’ roll and drift away ... ”

Dipping under bridges and passing the Flats’ flashy riverside bars and apartments, the boat creeps steadily, no more than 2 mph, toward an imposing bend.

“Columbus Road can be tricky,” Weber says. “The current can catch you there.”

Weber is self-assured, standing at the main front-facing window of the room, wearing a ball cap and a quarter-zip, sleeves rolled up. Looking outside, the 31-year-old Northeast Ohio native speaks plainly about the day’s route.

“It’s challenging. It’s 6 miles,” Weber says. “Very crooked. Very windy.”

You wouldn’t know it, but he has navigated these 6 miles of the river’s serpentine curves just a handful of times.

“A lot of bridges, a lot of recreational traffic, a lot of commercial traffic,” Weber continues, as a voice from the Coast Guard station crackles over the radio, asking for an estimated time of arrival. “No two days are the same.”

Stepping onto the metal platform outside of the captain’s deck, a breeze drifts over me and the rest of the Mark W. Barker — this newest ship of bulk-carrying business Interlake Steamship Co. fleet of 11 freighters, and just one of three that’s short enough to make it down this tricky river.

The trickiest parts of the route are made a little less thorny by the specifications of the Mark W. Barker, or the “W,” as some of the crew calls it. The boat was designed just a few years ago to navigate the Cuyahoga River with ease. Christened in Cleveland in 2022, it’s the first ship the locally owned steamship company has debuted in more than four decades, and it’s outfitted with new technology and a new layout — and Cleveland’s twisted river, top of mind.