If you want to get to Gee's Bend, Ala., there's only one way in: Farm Road 29. The community of slaves' descendants used to be accessible by ferry from Camden, the county seat, but that route was shut down in the 1960s to deter residents from crossing the Alabama River to join Martin Luther King Jr.'s voting-rights campaign.

Born and raised in isolation, the people of Gee's Bend cherish traditions that hearken back to the years just after the Civil War. Their hand- and machine-made quilts are especially telling, as art collector William Arnett realized in 1998, when he saw — photo of a colorful quilt and went in search of its maker. Arnett's research led him to Gee's Bend, a community of 700 African Americans named for slave owner Joseph Gee.

The women of Gee's Bend learned to quilt from their mothers, aunts and older sisters who'd learned the craft because their families couldn't afford blankets. They began before dawn and worked well into the night, piecing together scraps from worn dresses, corduroy pants and flour sacks.

"The vast majority of these quilts were made out of necessity, and they were actually made from the very fabric of [the quilter's life]. That includes a lot of jeans — particularly the backs of jeans, because they picked cotton on their knees, so the fronts were in terrible condition," says Louise W. Mackie, curator of textiles and Islamic art at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where The Quilts of Gee's Bend is on display. The exhibit, which runs through Sept. 12, showcases more than 60 quilts by four generations of women.

--Since their work debuted in September 2002 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the quiltmakers have garnered comparisons to Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse for their bold geometric patterns and innovative approach to collage.

"[The quilters] never thought of themselves as artists,"Mackie notes. "They had a different purpose when they were making them, but they cared about how they looked. They obviously have a flair for shapes and colors and textures. Many of [the quilts] predate the artists to whom they've been compared."

Gee's Bend resident Mary Lee Bendolph, whose mother taught her to piece quilts at age 12, was stunned when Arnett took her to the Houston exhibition. "He called it art and I thought it was a funny thing — talkin' about art for a quilt." exclaims Bendolph, 68, who sold quilts for $5 to $30 each to help finance her son's college education in the 1970s. Today, her works go for $200 and up at an Alabama co-op.

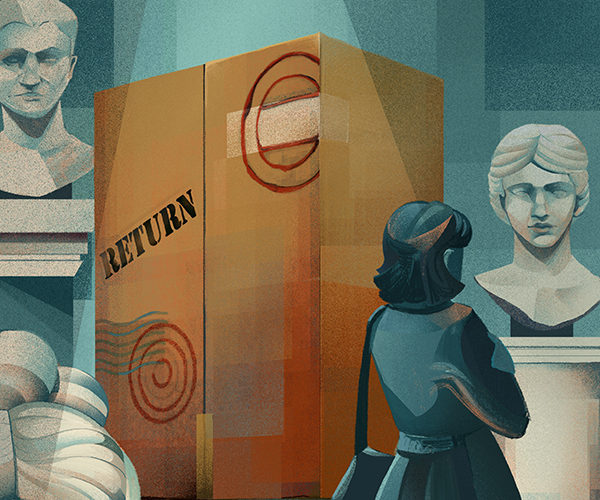

In the 1960s, Sears, Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdale's commissioned the quilters of Gee's Bend to produce multiple copies of their one-of-a-kind creations. But the women's improvisational approach to quiltmaking dismayed the department stores, which often sent back the quilts because they weren't exact duplicates of one another.

"These women are really independent and strong. They had quilt books with patterns in them, but they never wanted to follow them," Mackie says.