“Brel”: the Musical Revue That Saved Playhouse Square Celebrates 50 Years With Commemorative Plaque

by Anthony Elder | Apr. 10, 2023 | 9:00 PM

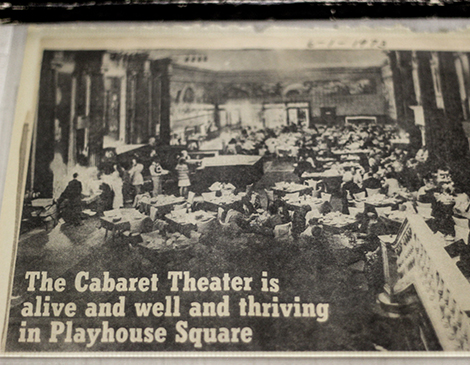

Courtesy Playhouse Square

Playhouse Square still stood in the early ‘70s, though just barely. The ceilings provided a constant snowfall of rotten plaster, stages sat in shambles as if struck by a bomb and demolition equipment stood outside of the marquees, ready to hammer the final coffin nail.

That is, until the musical revue Jacques Brel is Alive and Well in and Living in Paris proved that the arts were alive and well in Cleveland. The production, initially scheduled for a three-week run, garnered such a positive reaction that it ran for more than two years — becoming the longest-running show in the theaters’ history at the time and acting as a springboard for the venues’ survival.

Playhouse Square will honor the historic musical revue on April 18 with a commemorative plaque in the KeyBank State Theatre lobby.

“It really became a metaphor for the saving of the theaters,” says Joe Garry, host of Broadway Buzz at Playhouse Square and Brel’s original director. “And then the audience took up that marathon and wanted to help save it.”

Playhouse Square owes its last-minute rescue to Ray Shepardson, a member of the Cleveland Board of Education who scouted the theaters for a space to hold future meetings. Stumbling upon the Square, he knew it deserved more.

Shepardson began his revitalization with the formation of the Playhouse Square Association in 1970, hoping to attract local interest in the project. Yet, in lieu of the theater initiative, the Loew’s Building owner pushed forward plans to demolish the Mimi Ohio and KeyBank State theaters — for a parking lot.

Shepardson and his band of community leaders leaped into action again, obtaining a stay of execution, temporarily suspending the city’s permission to destroy the landmark.

The movement then received a $25,000 donation from the Junior League of Cleveland, and one Oliver “Pudge” Henkel was able to negotiate a five-year lease in the building. The Mimi Ohio and KeyBank State Theater lived to see another few years.

It was at this point that Shephard’s gears started turning faster. He envisioned a cabaret in the KeyBank State lobby space, whose main stage still needed serious repair.

“I walked into those spaces — they were in such disrepair it looked like bombs had happened,” Garry recalls. “The only pristine places were the lobby of the KeyBank State Theatre and the lobby of Connor Palace Theatre.”

So, Shepardson began the search for a show that could accommodate his lobby-turned-cabaret.

In his pursuit, Shepardson wound up attending the final showing of Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris at Cleveland State University. The performance, under the direction of Garry, struck him. After an unconventional initial meeting with the director, Shepardson secured his first show.

“Ironically, [Shepardson] sat next to my mother, and he'd beguiled my mother,” Garry says. “He was certainly a charmer. So, when we got home from the theater that night, she said ‘Oh! There's something I haven't told you. We have a guest for breakfast tomorrow.’ And I said ‘Who's that?’ She said ‘I invited that charming man Ray Shepardson.’ And I said, ‘Mother, he's a madman, are you crazy?’”

That madman, however, convinced Garry to direct the musical in his soon-to-be-refurbished lobby.

The work was hard and tedious — they needed to clean away piles of debris, hang large carpets and rugs to accommodate the acoustics and Garry remembers their handyman, a gentleman they called Smitty, sleeping inside Playhouse Square between bouts of tearing, building, drinking, cleaning and drinking some more.

After months of literal blood, sweat and tears, Brel kicked off on April 18, 1973. Tickets started at $7.75, including a buffet and a bottle of wine at every table.

Guests entered at the side entrance on East 17th Street to avoid the demolition machines sitting, almost threateningly, in front of the marquees. After making their way past mounted cops patrolling the street and leftover debris inside, patrons entered a world transformed.

“And it was magic,” Garry says, “because you stood up there and looked down at that brilliant space with those brilliant murals. And, you know, one of the most beguiling entrances to a theater in the world. Everyone made a grand entrance by coming down the staircase and going to their seats.”

As Garry remembers, the new cabaret attracted a who’s-who flock of Cleveland celebs. Brel became an instant hit with the audience and every week saw packed seats as word spread about the burgeoning hotspot.

By September 1973, the musical had showed 100 times in the lobby; in October, it took the title as longest-running Playhouse Square performance; and, finally, in June of 1973, the performance came to a close after more than 500 showings with roughly 800 fans every night — some of which came to see Brel more than 30 times.

Fueled by Brel’s success and income, Playhouse Square staved off demolition until it could grow back into the titan Cleveland knows today — the largest performing arts district in the United States outside of New York City with the largest community of Broadway season ticket holders in the country.

Now, walking into the KeyBank State Theatre, Clevelanders will notice the plaque commemorating the stakeholders, builders, actors, directors and patrons who kept Playhouse Square alive; an ode to persistence and triumph in a city where hard work pays dividends.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5