Bernie Kosar Always Gets Back Up

by Dillon Stewart | Jul. 18, 2024 | 9:00 AM

Kevin Kopanski, Mattew Nunes, AP Photo/David Dermer, AP Photo/Paul de Molina, AP Photo/Vernon Biever, Jerry Wachter/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images

"How did he look to you?"

The hushed question comes whenever you mention that you have interviewed Bernie Kosar. Since the former Cleveland Browns quarterback’s playing days ended in 1996, fans have watched Kosar — perhaps the most beloved local sports figure of the past 40 years — deteriorate. He’s struggled with addiction, the collapse of his marriage and financial woes. Obvious cognitive decline, which he’s openly attributed to head injuries from his playing days, has left him marble-mouthed and, at times, publicly disoriented. Just this year, he’s embroiled in two lawsuits for businesses gone bad.

Yet, sitting on the patio of his Chagrin Falls house on a warm summer evening, Bernie seems sharp and sturdy. Wearing a brick-red dry-fit shirt and black basketball shorts, the 60-year-old’s hands wave as he talks. He pretends to drop back for a pass or line up under center as he tells stories of ’80s glory. His 6-foot-5 frame towers over my 6 feet, 2 inches when he demonstrates how certain coaches would intimidate players. Sure, he rambles, but the empath is passionate about several causes, including the environment, the struggles of Appalachia, men’s mental health and, especially, holistic and natural remedies. If you give him time, he finds a point, often a convincing one.

The Chagrin Falls house we’re sitting outside is not his home. His home is a 38-acre wheat farm in Portage County with trails for four-wheelers and barns covered in solar panels and peace signs.

“I live high maintenance,” says Bernie. The famously low-maintenance celebrity immediately offers a laugh and a nah. “I need my space.”

This two-story structure is being converted into Bernie’s business residence. Inside, a Fat Head photo mural of a young No. 19 stretches across an entry-facing wall. Barrels of supplements sit on the floor and kitchen counters like a messy dorm room. Kosar is no longer the No. 19 in that photo. The mischievous smirk and glinting eyes remain, but pronounced laugh lines now frame the smile. Those famous black curls have fallen into neat, thinning brown-gray.

Bernie hands me a sampler of two pills called Addy. He sits on the board of the company, one of his few business ventures in the wellness space. The capsules contain a powder of raw coffee beans and two other botanical ingredients derived from Indian gooseberry. For years, Bernie was one of the more than 41 million people, as of 2021, who were prescribed Adderall. That number doesn’t include Vyvanse, Focalin or other prescription stimulants. Bernie’s high dose contributed to sleeping issues and anxiety. Addy claims its over-the-counter pills are designed to offer the same benefits, including focus and mental clarity, without the side effects.

Keeping track of all the doctors and researchers who have contributed to Bernie’s care is tough. But for the past few years, he’s worked closely with Dr. Michael Roizen, the emeritus chief wellness officer for the Cleveland Clinic and the founder of the hospital’s wellness institute, to build a personal health regimen. Roizen, whose resume includes co-authoring a book with TV’s Dr. Mehmet Oz and claiming people would soon be able to live to 160 years old, is a controversial figure. His philosophy revolves around lifestyle changes and — more recently — the potential powers of black coffee to detox and fight off inflammation and cognitive decline. This system has gone on to inspire a number of the products that Bernie is now hawking, including his Kosar Wellness line of vitamins, supplements and spray relief and Kosar Coffee, a $19 medium roast blend of arabica infused with resveratrol and vitamin D (both of which fight inflammation).

Bernie holds his hand parallel to the ground in front of me.

“Look,” he says. “No shake. Six weeks to two months ago, I would not have been cognitively present to sit here. I couldn’t have been here at 8 o’clock at night talking to you like this. I wouldn’t have remembered your name.”

Sitting here today, Bernie says he feels better than he has in years. Still, his health challenges remain more critical than ever.

Sometime between Thanksgiving and Christmas, University Hospitals hepatologist Dr. Anthony Post diagnosed him with cirrhosis of the liver, the third of four stages of liver disease. Post didn’t believe the Cleveland icon would make it through the year without a transplant. He was quickly placed on the liver transplant list and could be called to enter surgery any day.

Then, on Feb. 16, Bernie says an independent NFL doctor (meaning an expert that is not employed by the league) diagnosed him with Parkinson’s disease. Bernie’s personal doctors did not confirm this diagnosis to Cleveland Magazine, though they did point to symptoms associated with the early stages of Parkinson’s, including tremors, depression, anxiety, insomnia, stiffness, and impaired cognition and memory. Bernie says he’s been prescribed a number of pills for Parkinson’s — but he’s elected to replace most of them with Addy and Roizen’s program.

Objectively, Bernie’s liver and mental state have vastly improved since February. While Bernie credits his program with Roizen, there is no way to know if the improvement has come from these products and lifestyle changes or if he’s simply on a momentary upswing. Still, even Post says his recovery has been unprecedented.

The experience has emboldened Bernie to double down on natural treatments, often in place of traditional medicine.

Despite what he believes, these natural remedies are not proven medicine. But the scientific process takes time — time many don’t have. When you’re out of options, you turn to a Hail Mary.

But is Bernie scared that it’s the wrong call?

“Well,” he says. “I’d rather be wrong and be happy than be heavily medicated and miserable.”

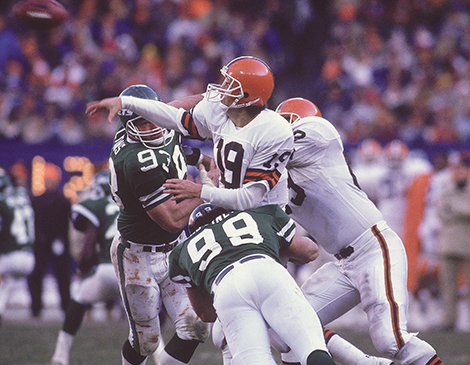

Bernie Kosar tastes blood as he lies on the frozen grass of Cleveland Municipal Stadium on Jan. 3, 1987. The New York Jets lead 20-10 in the fourth quarter of the Divisional Round of the NFL playoffs. Dog bones and drunken boos rain down from the Dawg Pound.

The quarterback has just been drilled in the back of the head by New York Jets defensive lineman Mark Gastineau, whose pressure has made Kosar’s life hell all game long. Cornerback Carl Howard, flying past the offensive line on a blitz, delivered a second shot to Bernie’s chin.

Bernie runs his tongue across an aching molar, realizing it’s gone. It was stupid to not wear a mouth guard, he thinks, but it’s too hard to call plays in those things. The quarterback sees stars — not for the first time today.

Earlier, a team doctor evaluated him for a concussion. “How many fingers am I holding up?” asks the doc. The test is rigged; everyone knows the number is always two.

“Once, before the doctor even held up his fingers, I said ‘two!’ He asked how I knew, and I said ‘I’m Nostradamus!’” he says. “I was out of it. Today, they would have taken you out of the game. That probably set off a domino effect of issues health-wise.”

He fumbles for the ammonia smelling salts he always keeps tucked in his pants and takes a huff. A rush of oxygen to the head. He gets back up.

In that moment, with four minutes left in the fourth quarter, staring down a first-round playoff loss for the second straight year, Bernie doesn’t know that he’s about to see a yellow penalty flag fall to the ground, marking a roughing the passer call on Gastineau that would give the Browns new life. He has no idea that his career-high 489 passing yards would lead to a game-winning field goal; that the two overtime contest would go down in NFL lore as the “Marathon by the Lake;” or that his heroics would solidify his local legend status.

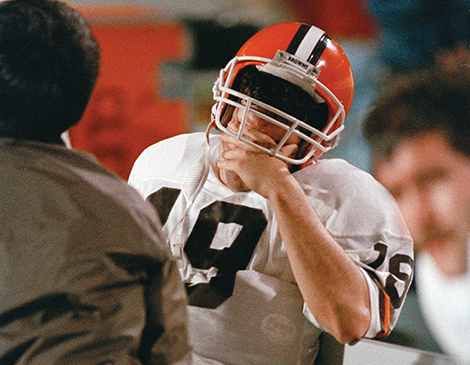

All Bernie knows is that he wants to die.

“When you’d come back to the sideline, the refs would [hold the first down markers upside down], and there was a big spear at the end,” he says today, standing up and tracing an imaginary measuring stick with his hands then imitating a dive. “I was so mad I tried to jump on it and impale myself because I literally wanted to die instead of have to go to the press conference because I felt like I had let everybody down.”

How could he not? The Youngstown boy grew up rooting for the Cleveland Browns. After a celebrated baseball and football career at Boardman High School, he became a Miami Hurricane, where a pass-heavy offense made him an NCAA National Champion and Orange Bowl MVP in 1983 and a finalist for the Heisman Trophy in 1984. He graduated early with a double major in finance and economics from the University of Miami School of Business.

Wanting to play for his hometown team, he deftly worked the system. After graduating early from the University of Miami School of Business with a double major in finance and economics, he opted for the supplemental draft, originally designed to create a pathway for those who faced ineligibility. Bernie’s early graduation opened a loophole that landed him in Cleveland. The Browns exchanged four picks over two years, including two first-rounders and a third-rounder, for the No. 1 pick in the supplemental draft.

Fame followed the Jets game: the “Bernie, Bernie” ballad, the covers of Sports Illustrated and a spread in GQ, the Ohio Edison commercial and the Converse ads. He was even on the freaking Wheaties box!

“For his friends,” reads a 1988 Cleveland Magazine feature by Jeff Hedrich called “The Reluctant Redeemer,” “going to a bar in the Flats with Kosar and hoping to be left alone is like lying out at Edgewater Beach with bread crumbs on your chest and expecting the gulls to respect your privacy.”

The self-described introvert — who comes off as a bit of a people pleaser — wasn’t comfortable in the spotlight. Friends and family describe the 20-something as shy and “skinny and geeky for a quarterback,” not the guy now being called on to, as the story puts it, be “the city’s salvation from its bum national image.”

“Who knows what some people see when they’re looking at me,” Bernie tells the magazine.

But in competition, however, he has always been comfortable.

“The one thing Bernie’s always known how to do perfectly,” Browns’ strength and conditioning coach Dave Redding tells Hedrich, “is beat you.”

Did that competitive nature combined with the pressure to win for his city push him past his limits and amplify that need to succeed?

“100%. I’m not sure that was healthy. Man, if I lose that (Jets) game …” he says, briefly trailing off. “Your whole dynamics of self-confidence and self-

esteem and self-worth massively change. And once you do it at that level, you become a-whole-nother level of a person in terms of competence — at the expense of your health.”

Injuries plagued Bernie starting in 1988, as did opiates, the league-wide trick to staying on the field.

On the night before a game, Browns staff would visit each player’s hotel room to make sure they were ready for bed and to hand them a cup of pills. These included sleeping pills, painkillers and, later, as the league began cracking down on opiates, “bricks of Xanax,” Bernie says.

Once Bernie retired from the league, the painkillers that once helped him fight through injuries evolved into a salve for insomnia, headaches, ear-

ringing and the pain he was experiencing — and a double-digit-a-day habit. During the next two decades, Bernie became as well as known for his slurred speech and erratic behavior as his on-the-field prowess. In 2006, divorce papers described addictions and bizarre behavior. In 2012, an interview with WKNR, the audio of which is no longer on the internet, made national news, described as “rambling and incoherent.” In 2013, he was charged with a DUI.

In 2012, just days after the sloppy interview, Dr. Rick Sponaugle contacted Bernie. Sponaugle, who runs Palm Beach’s Florida Detox and Wellness Institute, was known for controversial (and often vague) treatments for addiction and head trauma. A four-day trip to Florida preceded years of intravenous therapy with an undisclosed proprietary substance, which a former colleague of Sponaugle told The Plain Dealer could be a mix of vitamins, fish oil and other dietary supplements. In 2017, when he got clean, cannabis helped him overcome heavy withdrawals. These were some of Bernie’s first exploration of holistic treatment, but they would not be his last.

That year, former NFL linebacker Junior Seau, another of Sponaugle’s patients, committed suicide. The 45-year-old shot himself in the chest to preserve his brain, later confirmed to have CTE, for research. Seau is not alone among Bernie’s contemporaries. Dave Duerson, Jeff Alm, Rashaan Salaam, Charles Johnson and Greg Clark all experienced some combination of depression, anxiety, sleeplessness and addiction before taking their own lives. Others — including Marion Barber, Tony Siragusa, Shane Olivea, Phillip Adams, Demaryius Thomas and others — dropped dead from seizures, liver disease, strokes and addiction-related illnesses. More than 70 NFLers aged 50 or under have died since 2020.

At the time of Seau’s death, football’s connection to brain trauma and its connection to mental health issues weren’t as publicly known as they are today. But the long-term effects were well-known to Bernie. In all, he estimates that he’s had 40 surgeries, 80 broken bones, 100 concussions (diagnosed and undiagnosed) and 10 to 15 seizures.

A responsibility to speak out, not only about his experience but also about the treatments that were giving him relief, bubbled in Bernie. After all, his brain scans were showing rapid improvement, Sponaugle said at the time.

“There are hundreds, if not thousands, of guys who are dealing with issues and pain and stuff,” he says. “This [treatment] isn’t something I think a lot of guys know about, whether it’s the younger kids playing or the ex-NFL players. I don’t think a lot of people know there is hope for them.”

There must be something about the Jets coming to town. On Dec. 28, 36 years after that double-overtime victory, Joe Flacco has just solidified a 37-20 Week 16 win to clinch an unexpected playoff berth after a difficult 2023 season. But standing on the field, Bernie doesn’t feel like celebrating.

Sundays off the field have always been exhausting for Bernie, despite his love of the fans. Every groupie gets an autograph or a selfie. In luxury suites, drunk businessmen drape their arms around his broad shoulders and spit on his face as they scream in his ear. An anxiety powder keg for an introverted recovering alcoholic.

But today is different. He feels like he is going to faint. His friends have left, so he walks to his car alone. Ten feet feel like a marathon — let alone the trek from Cleveland Browns Stadium to his parking spot on West Third Street.

Days later, he is admitted to the hospital, where he spends more than 50 days over the next few months receiving blood transfusions and having fluid drained from his stomach.

The event isn’t a total surprise, though. A few weeks before the Jets game, Dr. Post diagnosed Kosar with cirrhosis. He tried to ignore it through football season. The Browns are heading to the playoffs. He is watching Kansas City Chiefs games with Travis Kelce’s parents and taking selfies with Taylor Swift.

Why slow down now?

When the Super Bowl rolls around in mid-February, Bernie tricks himself into thinking he’s strong enough to attend. His doctors tell him not to fly, but c’mon, it’s the Super Bowl. Vegas, baby! Tagging along with the Kelce clan. Podcasts to promote his businesses, especially his new one, Kosar Coffee.

How could he miss this?

“I’m a football guy,” he says. “So I flew out to the friggin’ Super Bowl, and it all hit me in the plane.”

Somewhere over middle America, Kosar passes out. When he gets off the plane, he finds his friend Dr. Mehmet Oz, a former colleague of Dr. Roizen. The physician, TV personality and fellow Cleveland native tells Bernie to go straight to the hospital. He spends the next three-and-a-half days in the intensive care unit.

“I was like, I can’t die in Vegas because nobody’s going to believe I wasn’t partying,” Bernie says with a laugh. “I have to at least die over Kansas or something.”

Luckily he doesn’t. Instead, he hops a private plane, courtesy of Union Home Mortgage owner and friend Bill Cosgrove. But Bernie knows he can no longer hide from his health problems.

Bernie is added to the liver transplant list just before Memorial Day. A patient’s status on the list is determined by the MELD Score, which estimates their chances of surviving more than three months without the surgery. Blood tests are entered into a computer, which spits out a number between six and 40. Like golf, a lower number is better. After Vegas, Bernie scored about a 15.

More than 60 years after the first successful liver transplant, surgeons and physicians are darn good at them. According to Post, Bernie’s liver doctor, 98% of patients leave the operating room alive and about 80% live more than five years. Considering most people have about three months to live by the time they get a transplant, those are high rates of success.

The effects of liver disease do not stay within the three-pound organ. Located in the upper right portion of the abdominal cavity, the liver is kind of like the body’s garbage disposal, filtering toxins from the blood and readying them for excretion.

A liver not working correctly can wreak as much havoc to the body as Gastineau did to the backfield of that 1987 game, causing cognitive dysfunction, internal bleeding, retention of liquids and many other symptoms.

“Obviously there can be complications, but usually within hours of putting the new one in, they start getting better right away,” says Post. “They’ve been so sick that the body just loves having it there. A lot of patients say, ‘I didn’t know how sick I was for the past 10 years.’”

In addition to taking diuretics, water pills and two other pills designed to lower his toxin level, Post directs Kosar to focus on his diet. He suggests 60-100 grams of protein a day to combat muscle wasting. Second, ditch the salt shaker; less than two grams of sodium a day. Fresh fish. Fresh meat. Fresh veggies. It goes without saying: no alcohol or drugs.

As of late June, Bernie’s MELD Score has dropped to about 10. Post attributes that to the common fluctuation of liver disease.

“People with chronic liver disease can get very sick very quickly,” says Post. “Some people need a transplant right away. Others have a fluctuating course. But eventually, they’re going to need a transplant either way. Bernie seems to have a fluctuating course as opposed to somebody with a downward spiral. When I first saw him, it looked like he was just gonna go downward and wasn’t going to survive a year, but he seems to have kind of come back nicely.”

Bernie, of course, attributes his recovery to the wellness program he’s developed with Roizen, especially his coffee-based products. The doctor, who drinks 7-8 cups of black coffee a day, truly believes coffee is the key to detoxing the body.

While Post isn’t so sure about some of the unproven alternative medicines Bernie purports — “I’m not sure how scientifically valid they are,” he says. “They have, maybe, some theoretical benefit” — he does cite promising research that suggests those who drink about three cups of coffee a day show a slower progression of liver disease than non-coffee drinkers. Decaf offers about 50% of the benefits that the caffeinated version does, Roizen says.

“We don’t know what it is in coffee; it’s probably partially the caffeine and partially the polyphenols,” Roizen says. “But it’s the best thing we know of at healing the liver other than God and genetics.”

Doctors cannot confirm what caused the liver damage. Bernie does have a history of drug and alcohol abuse, and according to a study by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, about 50% of cirrhosis deaths in 2019 were alcohol related. But the resilient liver also regenerates, and Bernie has been sober for about seven years. The QB believes nearby fracking and pesticides on his farm have contributed to his condition. According to Roizen, tests revealed unprecedented levels of organic solvents that have been tied to pesticide poisoning.

“We don’t know what caused it,” Roizen says. “He did have a problem with alcohol and other drugs. It could have been those things, but the organic solvent that got in his blood was at a level that could cause liver rot, as well.”

Even if Kosar does overcome liver disease, he must eventually face the Parkinson’s diagnosis. Before being placed on the transplant list, Post, who did not confirm the Parkinson’s diagnosis, had his team of neurological experts assess Kosar. The team determined he was fit to have a transplant. In addition to diet and physical exercise, Roizen has given Bernie a list of 40 ways to manage cognitive function, including limiting stress and speed-processing exercises. He’s also taking about 17 supplements that promote brain health, according to Roizen.

As the sun sneaks away after nearly three hours on the Chagrin Falls patio, my energy has waned faster than Bernie’s. Comprehending the complexities of his medical situation is exhausting, but his excitement, or maybe fascination, invigorates him.

It’s an opportunity, he says. His fans are aging, too.

Maybe he can offer them a new kind of hero, one who helps them find wellness and confront their health challenges with optimism. In fact, he is forming a company called Kosar 19 with that in mind.

Sixty-five percent of men report being hesitant to address mental health issues. Maybe opening up about his mental struggles can prevent an overdose or suicide.

“I want to spread that message. People are so sad and depressed. I want to give people hope,” he says. “It’s tough to talk about. But now as I enter the fourth quarter of my life, it almost feels like a responsibility.”

Bernie Kosar certainly has regrets. But playing football isn’t one of them. Not for a second. After all, the game taught him his greatest life lesson.

“You don’t lay on the ground,” he says. “You just are gonna get up. Like now, I’m not going to quit on this stuff. I had fun with the concussions and getting up and not quitting, and I’m going to have fun with this.”

Dillon Stewart

Dillon Stewart is the editor of Cleveland Magazine. He studied web and magazine writing at Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism and got his start as a Cleveland Magazine intern. His mission is to bring the storytelling, voice, beauty and quality of legacy print magazines into the digital age. He's always hungry for a great story about life in Northeast Ohio and beyond.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5