One image sticks in Amy Poder’s mind about the day her daughter, Toree, died last September.

Just a few weeks away from her 16th birthday, Toree was at Akron Children’s Hospital. She had been treated for Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, a congenital disorder that affects the lymphatic and vascular system, and was suffering from a deadly infection.

Amy had just returned to the room after making phone calls to break the news to others. “Dr. [Sarah] Friebert was sitting at Toree’s bedside, holding a can of pop with a straw in it, feeding her a can of Coca-Cola,” says Amy.

It was one of her final requests, the last thing she ate. Toree died less than an hour later.

The Coke can sits on the dresser in Toree’s room. To Amy, it represents more than her daughter’s final moments before dying, it signifies the compassion, caring and support she received from Friebert, the physician who became an integral part of the family’s life during the final five years of Toree’s treatment.

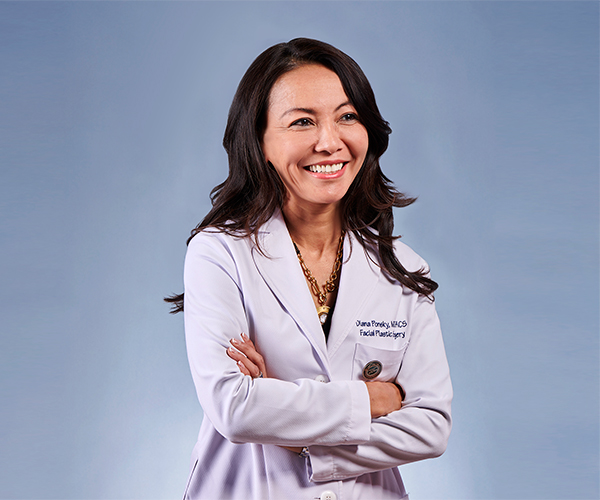

As director of the Haslinger Family Pediatric Palliative Care Center at Akron Children’s Hospital, Friebert helps coordinate all aspects of care for a child with a life-threatening illness, including any help the family needs. The program goes beyond medical care to include help with psychosocial, emotional, spiritual and financial issues — what Friebert terms A Palette of Care.

Friebert launched the program at Akron Children’s Hospital about five years ago. She estimates between 40 and 80 percent of children’s hospitals in the country have some type of palliative care program available for families. And 75 to 90 percent of children who die in the United States do so without benefiting from any type of palliative or hospice care.

She’s helping to draft legislation for Ohio that gets insurance to cover palliative care services so that children can have concurrent palliative care and curative care. “Palliative care really is about symptom management,” Friebert explains. “It’s about quality of life. It’s not about death. It’s about living.”

Many of the children in her care go on to “graduate” from the program, cured. But she is inspired by the journey she takes every day with children and families. Even if a child dies, she works with the family “forever,” she says, because bereavement doesn’t end at a certain time on the calendar.

“Lots of times kids who live a very short time bring amazing gifts to their families even when they’re not here chronologically very long,” she says. “They do more in the time that they’re here on the earth than most of us do in 85 years on the earth. And we get to be witness to that which is really an incredible miracle in and of itself.”— Heide Aungst