LaKiesha Bob sits on the examining table in MetroHealth's obstetrics unit. Her hair is pulled back ballerina tight, and her feet jiggle nervously against one another. A black hooded sweatshirt hides her newly swollen stomach.

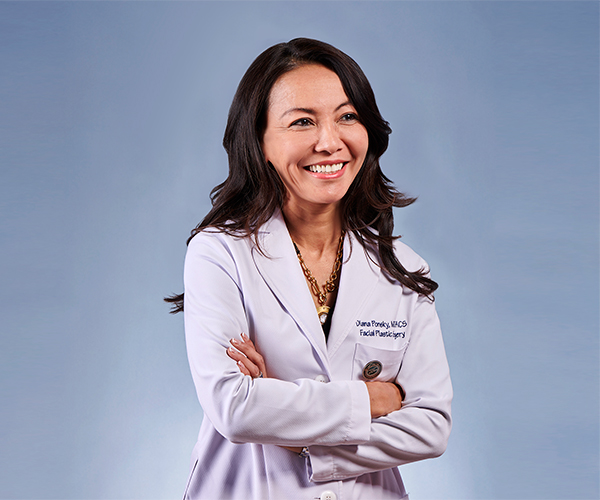

The 21-year-old just received the news she is carrying twins and is still digesting this information when Dr. Jennifer Bailit, wearing a purple turtleneck and a warm smile, strides into the room.

"Have you made the phone calls yet to tell everyone you're having twins?" Bailit asks.

Bob shakes her head no.

"Well, that will be fun," Bailit says. Then her face turns serious. "I understand you had a tough delivery a while back."

Bob looks down at her lap and nods.

Four months ago, Bob went into early labor. She was only 21 weeks along when she started bleeding. She was hurried to the hospital, where she delivered 19 weeks early. The baby died shortly after.

"We don't want what happened to you to happen again," Bailit says, looking straight into Bob's eyes.

The main treatment question, Bailit says, is whether Bob should be given a series of shots called 17P. The drug is known to help prevent preterm births for those who previously have had a preterm birth, but it hasn't been studied much on twins yet.

"We don't have to make the decision now. We've got a few weeks. I will make a few phone calls and do some more research," Bailit says. She smiles as she stands up to leave. "In the meantime," she adds, "I realize the one thing I haven't told you is that twins are really fun. I've got two of them at home. Now go home and make those phone calls!"

What the doctor didn't tell Bob in the consultation was that if it were not for Bailit's own efforts, the drug 17P, which has been shown to reduce the rates of preterm births by 33 percent in women who previously had a preterm birth, would not have been a possible treatment option for her.

In 2003, MetroHealth was one of 20 hospitals participating in a National Institutes of Health study on the validity and cost effectiveness of 17P in preventing preterm labor for pregnant women who had previously experienced premature births. Bailit authored the 2007 summary article, which showed that weekly injections of 17P was a cost-effective means of preventing early labor. But at that point, the drug was not yet FDA approved for this purpose.

Four years later, KV Pharmaceutical arrived on the market with a federally approved version of 17P called Makena. Bailit was thrilled — until she heard that the company planned on charging $1,500 per injection. It cost $10 to $20 to produce. That was an increase of 14,900 percent.

Bailit was outraged. "I'm not opposed to drug companies making a profit," she says. "But no one could afford the drug [the way KV priced it]."

So Bailit, a nationally known crusader for mother's rights, held a press conference with Sen. Sherrod Brown. Brown, in turn, started a campaign to convince the drug company to change course, sending protest letters to the company's CEO and asking the Federal Trade Commission to open an antitrust investigation.

The protest worked. Last April, KV Pharmaceutical dropped the cost of the drug by more than half.

Bailit has since turned her attention to the issue of early deliveries. In recent years, there's been a trend of pregnant women asking doctors to deliver a few weeks early because they are uncomfortable or they want to make sure their doctor is available.

"As neonatal medicine has evolved over the last decade, we've seen more and more miracles [of premature babies surviving]," Bailit says. "People got cavalier as the fear of premature births disappeared."

But Bailit believes this is dangerous. Babies born even two weeks early have an increased risk of jaundice, breathing problems and death, she says.

In 2008, Bailit, who holds a degree in public health, helped lead a statewide initiative to bring down the rate of inducing births before 39 weeks unless medically necessary in 20 hospitals around the state. In one year, Bailit and her collaborators helped reduce the rate of preterm births by 60 percent. "To the extent that I can help it, I want every mom to have a healthy baby," Bailit explains.

It is this guard dog mentality, coupled with a strong compassionate nature, that makes Bailit so inspiring. "[Dr. Bailit] really listens to her patients," says Dr. Ted Waters, Bailit's colleague in maternal fetal medicine at MetroHealth. "She really understands the balance between pregnancy and delivery in very high-risk patients."

It's a temperament Bailit displayed later on while consulting with 32-year-old Christine Markley, who is in her 37th week of pregnancy and feeling miserable. There's a reason for this, Bailit says. Markley's baby weighs almost 10 pounds.

"Oh no," says Markley, who planned on a natural delivery without an epidural. "I can't do that. I need to deliver now. Today."

"I know you're uncomfortable — and if your blood pressure was hiked, we'd deliver now," the doctor says with a patient smile. "But there's no reason to deliver you yet. We need to get you to 39 weeks."

Markley tries appealing to Bailit's sensitive side. "I can barely walk," she pleads. "I can't hardly get out of bed."

Faced with the doctor's sympathetic but unyielding stance, Markley gives in, and settles for a delivery date two weeks later, at full term.

It's a small victory for Bailit, but one she will continue to push for.

"There are a lot of ways to change the world," Bailit says. "I just want to clean my own little corner. My corner happens to be premature pregnancies."