Why Cleveland's Guardians of Traffic and Its Baseball Team Are Forever Linked

by Vince Guerrieri | Mar. 14, 2022 | 12:00 PM

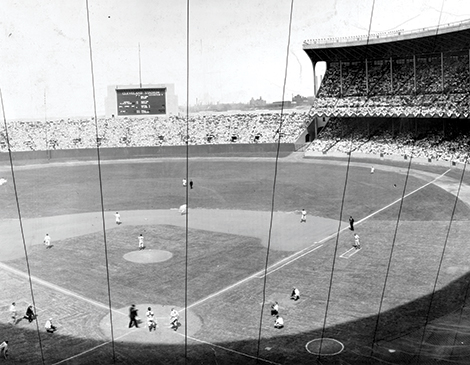

Wil Lindsey, Courtesy Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library Special Collections

Although it was the Indians’ 100th game of the season, the festivities surrounding their game against the Philadelphia Athletics on July 31, 1932, were on par with any Opening Day ceremony.

And in a way, it was opening day. It was the Cleveland Indians’ first game at their new home. Following the previous day’s loss at League Park, team and municipal officials sat at home plate and formally signed the lease for the Indians to begin play at the new municipally built lakefront stadium.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium was a crowning achievement for Osborn Engineering, the Cleveland company that had risen to prominence building the new concrete-and-steel ballparks that had started to dot America’s big cities. And it was a tribute to Cleveland, which by 1930 had become an industrial powerhouse and the sixth largest city in America, its population over 900,000.

Old-timers were introduced. Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis spoke. Attendees included Ohio Gov. George White and Louisiana Gov. Huey Long. (The Indians held spring training in New Orleans, and Long held a ceremonial share of stock in the team.) The weather was perfect as Cleveland’s Mel Harder found himself on the short end of a pitchers’ duel with Lefty Grove. The Indians lost, but it looked like they’d found their new permanent home, which was larger and fancier than their home at East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue.

By comparison, four months later, the other big project in Cleveland of that era opened with little fanfare. At 4:53 p.m. on Dec. 2, traffic barriers were moved aside, and motorcycle police officer John Frantz led traffic across the new Lorain-Carnegie Bridge. The long-awaited span across the Cuyahoga River, linking downtown to Ohio City, was built to alleviate traffic on the other high-level bridge, linking Detroit and Superior avenues. Among the flourishes were four pylons of Berea sandstone, with statues on each side, chiseled by Italian artisans who had made Cleveland their new home. The Guardians of Traffic would look down on the vehicles that crossed the bridge — another symbol, like the new stadium, of how far the city had come.

Sign Up to Receive the Cleveland Magazine Daily Newsletter Six Days a Week

(Courtesy Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library Special Collections)

Both projects were funded by bond issues passed by residents. The fortunes of the bridge and the stadium — and its main occupants, the baseball team — have risen and fallen precipitously over the decades but followed similar arcs. And starting this spring, the bridge and the baseball team will be inextricably linked, as the team for the first time since 1915 will take the field with a new name: the Cleveland Guardians.

RELATED: Iconic Cleveland: The History Behind Cleveland’s Guardians of Traffic

The ideas for a municipal stadium and the bridge date back decades before their actual construction. Voters passed an $8 million bond issue in 1927 for bridge construction and a $2.5 million bond issue the following year for the stadium.

But the fact is neither was particularly well-received, at least initially. Traffic remained mostly unchanged across the Detroit-Superior span, and the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge was referred to in print as a white elephant, as it was prone to bottlenecks — specifically on the West Side — until it was widened years later.

And Cleveland Stadium didn’t make fiscal sense for the Indians. In the throes of the Depression, many thought it made more sense for them to play in the stadium they owned — League Park — than the one they had to lease, and they quickly returned to East 66th and Lexington. Ironically, when Cleveland Stadium hosted the 1935 All-Star Game, it was the only major league game at the stadium that year.

Ultimately, the Indians divided their time between League Park and Municipal Stadium until Bill Veeck bought the team. Starting in 1947, the Indians would make Cleveland Stadium their full-time home. (By then, it was also home to a football team in a new league challenging the NFL. The league, the All-America Conference, lasted just four seasons, but the team — named for its head coach, Paul Brown — was able to make the jump to the NFL starting in 1950.)

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Browns and Indians were the class of their respective leagues, playing in the newest stadium in pro sports. Overall, the city of Cleveland was booming, as well. Seven years after the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge opened, another high-level span crossed the Cuyahoga River, as part of the city’s new Shoreway. The Main Avenue Bridge construction was led by a dynamic new employee in the county engineer’s office named Albert Porter.

The sky seemed to be the limit for Cleveland, which was being touted as the “best location in the nation.”

By the 1970s, things had turned bleak, due to a variety of factors, including deindustrialization and racial strife. Cleveland was being maligned as the “mistake on the lake,” where the river caught fire. The Indians’ fortunes had declined precipitously. In 1973, the Opening Day crowd of 73,000 represented more than 10% of the team’s total annual attendance. The following year, the team became notorious for forfeiting a game, after mounting a furious comeback, as the result of a fan riot during a 10-cent beer night promotion. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the team was linked to cities looking for a major league team, conducting serious negotiations in Seattle and New Orleans.

RELATED: Tristan Thompson In Conversation With Darius Garland

(Courtesy Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library Special Collections)

Things were faring little better for the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge. It remained a well-used thoroughfare, with more than 25,000 cars crossing it daily, but contemporary reports said it had “more patches than a quilt.” Plans were made for the bridge’s repair — and widening, from four lanes to six. But to do so would mean removing the historic pylons. And that was just fine with Porter, by then the Cuyahoga County engineer. Porter, diplomatically described by the Cleveland Press as “no respecter of beauty” and for a time the county Democratic Party chairman, led the charge for freeway construction after World War II and even tried to pave over Shaker Lakes — which he derided as a “two-bit duck pond” —with a highway.

RELATED: 10 Cent Beer Night: An Oral History of Cleveland Baseball's Most Infamous Night

“Those columns are monstrosities and should be torn down and forgotten,” Porter said of the Guardians of Traffic, which he also referred to as “gargoyles.” “There is nothing particularly historic about them.”

Fortunately, historians disagreed, and the bridge was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Porter ultimately lost his bid for re-election that year after details emerged of his 2% club, with employees kicking back that much of their salaries to him. He died in 1979, still on probation after pleading guilty to 19 counts of theft in office.

The bridge closed in 1980 for a three-year, $22 million restoration, and when it opened, it had a new name: the Hope Memorial Bridge, named for the family of Harry Hope, one of the stonecutters who helped build the bridge. His son Leslie Hope — better known as Bob — became one of the biggest stars in America. At various times in the team’s history — none particularly fruitful — he was a minority stockholder (when times were bad, team ownership always wanted him to buy more stock).

And on Oct. 3, 1993, Bob Hope sang “Thanks for the Memories” after the last Indians game at Cleveland Stadium. The team’s tenuous fortunes, like those of the bridge, had been solidified. A new stadium was being built on the site of the Central Market — within sight of the bridge and its Guardians of Traffic.

The team and the Guardians were linked geographically. And starting this spring, more than that.

“We hold tight to our roots,” Tom Hanks narrates in the video announcing the name change, unveiled last summer. “And set our sights on tomorrow.”

For more updates about Cleveland, sign up for our Cleveland Magazine Daily newsletter, delivered to your inbox six times a week.

Cleveland Magazine is also available in print, publishing 12 times a year with immersive features, helpful guides and beautiful photography and design.

Vince Guerrieri

Vince Guerrieri is a sportswriter who's gone straight. He's written for Cleveland Magazine since 2014, and his work has also appeared in publications including Popular Mechanics, POLITICO, Smithsonian, CityLab and Defector.

Trending

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5