Thomas* is 27 minutes late for our meeting at the McDonald’s on West 117th Street in Lakewood. It’s Friday afternoon, and his arms are flecked with dirt. He’s wearing a short-sleeved peach button-up over a gray Cleveland Browns T-shirt.

At first, Thomas’ eyes are glued to his iPhone as he sits quietly in the corner booth across from the front window. He’s nervous about the weekend. The 36-year-old is a handyman for hire who does one-off repair jobs and flips equipment at scrapyards and pawnshops for cash.

During the week, it’s easier to make money when businesses are open. But the weekend is a dead zone, leaving him little money to live off of. It means he has to plan ahead.

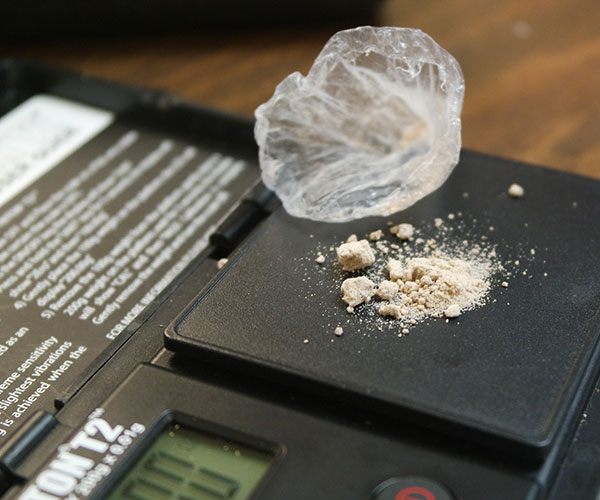

So, he’s waiting for a phone call from a connection in Westlake who will hopefully sell him a half-gram of heroin, equivalent to three shots, for $70. It’ll be enough to get him through the night.

“I don’t know how tomorrow is going to go,” he says, lifting his head to stare out the window at the line building in the McDonald’s drive-thru. “If I didn’t take it today, somebody would be scraping me off the floor of this place.”

He admits to injecting heroin in his arm an hour before our meeting. When he describes the euphoria that holds him in place after injecting the drug, his eyes glaze over, his breath becomes shallow.

“The silence is quieter than any Christian prayer,” he says, pausing for a moment. “But the end result is going to be the badness that everybody has found. There’s absolutely no way out.”

Thomas developed an addiction to Vicodin and Percocet after having two oral surgeries at age 15. When he exhausted the ability to get prescription painkillers, he turned to heroin, snorting it for the first time as a 16-year-old in the backseat of an older friend’s car near a downtown strip club.

“Fifteen to 20 years ago, a dosage would keep me well and without withdrawal for at least 12 hours,” he says.

But the drug market has changed. Dealers rarely sell pure heroin. Now that fentanyl and other synthetic opioids have been introduced into the heroin chain with a much higher level of potency, Thomas says the effects don’t last nearly as long. The symptoms of withdrawal — nausea, dizziness and diarrhea — begin just five hours after a single shot.

So Thomas injects heroin into his forearm about every four hours.

“It’s dangerous all around, but for someone who is doing this every day — morning, noon and night — it’s different than someone who just wants a kick,” he says. “There’s no kick in this.”

He’s had periods of sobriety before. When he was 28, he fell asleep at the wheel and ran a red light on the West Side, colliding with four cars in the middle of an intersection. He checked into detox and entered inpatient programs at Catholic Charities’ Matt Talbot for Recovering Men and St. Vincent Charity Medical Center’s Rosary Hall. It was the beginning of six years of sobriety.

“I remember getting clean and getting straight and being in the mindset that my addiction, my usage could be ancient history,” he says.

But when his father died suddenly from cancer in 2014 and Thomas started having severe abdominal pain, he relapsed.

“Sometimes I shake myself like, When am I going to wake up from this nightmare?” he says.

He’s trying, but the detox facilities he’s sought out in Cuyahoga County won’t take him because he lacks proof of residence. He won’t talk about where he lives or his family members, some of whom aren’t aware he’s still struggling with addiction.

Suddenly, Thomas perks up, eyes wide. He runs outside and greets a younger man in gray sweats with a cigarette hanging off his bottom lip. For 10 minutes, the two men talk, pulling out their cellphones and exchanging numbers. When Thomas returns, he apologizes. He hasn’t seen his friend, who just got out of the Lorain Correctional Institution, in years. Thomas wanted to know who the man was dealing for now that he’s free.

“If I can get five days clean, I think I can have it,” says Thomas.

“But that’s a good example,” he says, pointing to the man in sweats. “This guy gets out and he’s clean, you know? I mean, I guess, the call is that strong.”

*Cleveland Magazine has changed his name to protect his identity.