We’re not out of the opioid crisis, but the tides may be slowly turning.

There were 727 total drug overdose deaths in Cuyahoga County in 2017, which represents a 9 percent increase from the year before, according to the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s 2017 Preliminary Drug Deaths Report.

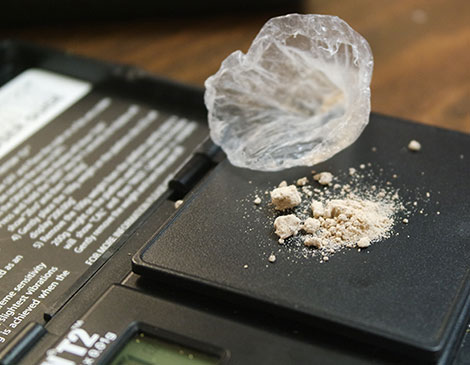

But it’s a stark difference from the 80 percent increase in overdose deaths between 2015 and 2016 sparked by the introduction of fentanyl into the local drug trade. A lab-made opioid, fentanyl is up to 100 times more potent than morphine and is often being mixed with heroin, powder and crack cocaine, and marijuana.

“The emergence of fentanyl really was a game changer in a lot of ways, because it’s a far more potent drug,” says Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner Thomas Gilson.

Fentanyl’s rise has inspired a cross-county collaborative among law enforcement, public health officials, local hospitals and community organizers to address the opioid crisis as a public health epidemic. Although Gilson believes these efforts have helped slow the increase in overdose deaths, there’s still much work to be done.

“There’s a perception out there that we’re getting ahead of the problem,” says Gilson. “I’m reluctant to fully sign off on that, because a 9 percent rise is still not trending in the right direction.”

Here’s three things you need to know about the ongoing crisis.

The opioid crisis has been evolving. “I see it as three chapters,” says Gilson. “You had the prescription opioid phase, the heroin phase and the fentanyl phase.” When Cleveland Magazine told the stories of 194 people who died from heroin overdoses in 2013, fentanyl wasn’t yet on our radar. In 2017, it accounted for 492 of the overdose deaths. The introduction of carfentanil — a tranquilizer powerful enough to put down a 12,000-pound elephant — has also complicated matters. With 54 overdose deaths in 2016, it has now tripled to 191 overdose deaths last year. “That needed a different response than just shutting down production,” says Gilson.

We needed to look at the opioid crisis as a public health problem. With the help of MetroHealth System’s Project Dawn, emergency medical services and local police departments started carrying naloxone, also known as the brand name Narcan, a life-saving opioid blocker that reverses the effects of an overdose and revives a victim upon inhalation. In 2017, Project Dawn patients reported administering Narcan in 537 cases, while the Cleveland EMS administered 7,745 Narcan doses. “Naloxone is the best investment our county executive and the other county folks made in the crisis,” says Gilson. “From a public health perspective you’re saving lives and accepting not everyone is going to be cured by that so much as their life will be saved and the cure hopefully comes later.”

Solving the problem will take more collaborative effort. “One thing that has become apparent is maybe it’s time for another summit,” says Gilson. In 2013, U.S. Attorney Steve Dettelbach joined the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Division of Police, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI and the Ohio State Medical Board in an all-day conference calling the opioid crisis “a crisis for all people.” “He was dead-on right that maybe we were too siloed and the people in law enforcement didn’t necessarily work well with people in public health and we needed a bigger approach to that.” Since then, the conversations have continued, and Gilson says it’s time for redirection. “There’s talk that this fall we’ll revisit a new summit to kind of refocus efforts,” he says.